Download the PDF.

Is the Labour Power a Commodity?

Perhaps, the most promising approach to our problem would be to revisit the traditional definition – rather implicit with Ricardo, thoroughly explicit with Marx – of the wage as nothing else than the price of a commodity sold by its owner, the wage-earner, and bought by the capitalist, just like any other commodity.

Not that the wage – according to Marx – isn’t at the same time a factor – the most elementary one – of the distribution of income. But the question could arise whether it is directly so, in the same way as, for instance, rent or interest, (the latter in so far as it is distinct from “pure profit”), or indirectly so, that is, only as a consequence of the fact that the exchanged commodity is the only saleable thing the working class possesses, and that the proceeds of this sale are its only income.

In the first case, we might indeed need a particular theory to explain the variations of the wage, just as we need one to explain the variations of rent or interest. In the second, we only need to insert the wage into the general theory of value, our problem being henceforth reduced to analyzing the possible factual specificities of its object as compared with all other commodities and of its producer as compared with all other producers.

Marx chose the second solution. What the worker supplies to his employer is a genuine commodity and what he receives from him a genuine price. As such, the wage is, in the long run and on the average, determined by the value underlying the commodity it buys, that is, the labour time which is socially necessary to reproduce it.

On that same basis, two major theoretical problems were left unsolved by Smith and Ricardo: eliminate the absurdity of the labour measuring its own value, on the one hand; reconcile the generation of a surplus with the general principle of equivalence, on the other.[1]

As it is well known, Marx solved the first problem by distinguishing between labour and labour power, and the second, by distinguishing between value and use-value of the latter.

However, when looking at these Marxian achievements, one cannot help thinking that, remarkable as they were on the theoretical level, the only purpose they were of use for was to recover the internal symmetry and coherence of the system after its perturbation by the introduction into the club of commodities of something as essentially different from all other commodities as the human vital, power, i.e. the man himself. From then on, one is inexorably induced to question the usefulness of the whole exercize: perturbing and re-harmonizing altogether.

In his “Value, Price and Profits” Marx strongly emphasized that the only scientific way to explain profits is to show their consistency with the exchange of equivalents and in “Wage-labour and Capital”, a systematic re-writing of his Brussels Conference of 1847, he insisted that the labour power is a commodity subordinated to this general law of equivalence. He made it clear that he considered the wage, not as a part of the output, but as the price of the labour power, of the same nature as the price of any other input.

However, in various subsequent writings, pending the special book on the wage, initially planned and never written, Marx was obliged either to qualify explicitly this early definition of his or supply some hints for such qualifications.

1) As the capitalist mode of production (CMP) is developing, all commodities are liable to being produced capitalistically except one: the labour power.

It follows that under capitalist conditions the value of all commodities contains a surplus value created in the process of their production; the labour power, sole source of surplus-value in the CMP, does not contain itself any surplus-value at all.

The cause of this difference is of course that, contrary to all other commodities, no living labour (sole creator of surplus-value) is used to produce the labour power itself. Capital as such does not participate either. Only “raw materials” – subsistence goods – are transformed into vital force and pass their value on to it. To be sure, a sum of money is necessary in order to obtain these materials. However, at the moment the worker has this money in his pocket, this is no longer capital but revenue.

Naturally, the value of these materials itself does contain a surplus-value, but this had been created previously, during their production process, and although h it would be incorrect to describe them as “constant capital” s it is nevertheless certain that they constitute a constant element of the cost and cannot create an additional surplus-value during the process under consideration, i.e. the process of “production” of the labour power.

It, therefore, follows that the labour power is the only commodity whose value can in no way be transformed into price of production.[2]

Finally, it becomes clear that the biological process of the transformation of the wage goods into muscles, nerves and brains has very little in common with the process of social production of commodities.

2) The law of value implies that the “independent producer” can freely move from one industry to another according to the fluctuations of market prices around respective values. No such “mobility” exists for the producer of the labour power. The only means he has to force the wage up or down, in order to bring it into line with the value of his exclusive commodity, i.e. to make the law of value operate, is to underproduce or over-produce this same commodity, but this is materially impossible without overproducing or underproducing himself. Eventually, the law of value applied to the wage can only work through some Malthusian mechanism. Then, all the well known aberrations, perversities and cumulative effects of the function population/subsistence-level come into play. However, if, on that ground, one can understand the indignant condemnation by Marx of the “iron law” of Lassalle, one cannot sea clearly how the labour-value could equilibrate the labour market without the mediation of that “law”.

3) To the extent that pre-Marxian classics had stuck to a biological datum, they were obliged to present conclusions consistent with their premises, however questionable the latter might be. But Marx watered down, the biological datum with a historical datum. What then determines this “moral and historical element”? The vague reference to the “degree of civilization” arrived at by the society does not answer the question. For no degree of civilization can ever be arrived at without a corresponding previous level of consumption, that-is-to-say, without a previous level of adequate wages. At the limit, as Ronald Meek rightly observes, the value of this years’ labour power is taken as equal to the previous years’ wages.[3]

In a given place and a given epoch the value of the labour power is given, says Marx. Does that mean that the wage is not a problem of the Political Economy and that the theory Bienefeld demands will not necessarily be an economic theory? Well, but what exactly is given? Is it the basic wage for the lowest-grade simple labour or the whole assortment of wages for all grades and professions?

The “moral and historical element” makes of the “socially necessary level of income” (Bienefeld) a substitute for the “socially necessary labour”. Besides the fact that this very substitution strips the labour power of its commodity-like appearance, it makes the “reduction” problem still more inextricable .

4) Marx admits that the historical element does not combine organically with the physical element but is just added up to it. The “ultimate limit” is determined by the physical element. Above that, the value of the labour power is determined by the traditional “standard of living”.[4]

Now, this is an unintelligible proposition. The value of all commodities is the socially necessary labour time to produce each one of them. This is nothing else than the “physical ultimate limit” below which some producer goes out of business and the supply falls short of the demand. What obliges the buyer (employer) of this particular commodity, the labour power, to pay for it an extra “traditional charge”?[5]

There are, however, some still more awkward shortcomings which arise from taking the labour power as a commodity.

5) Even at the “ultimate physical limit” there is no direct correlation between a necessary labour time incorporated in the subsistence goods and a certain average quantity of labour power produced out of a certain assortment of these goods. Subsistence goods do not produce the labour power directly but indirectly through producing the worker (and his family). The final yield of this “breeding” depends on the length of the working day and the length of the active life. Between this ŭse-value of the labour power and its value in terms of the necessary inputs, there is no proportionality. This circumstance would make no difference if the employer was as free to use the “commodity” purchased in an optimizing manner as were the slaveowner or the horsebreeder. In that case, we would have to take the length of the working periods and the intensity of the work as constant, so as to be able to determine the value of one unit of average labour power in the same way as we were able to determine the value of one average slave or one average horse as soon as it was granted that their owner would squeeze either of them in the most “rational”, objectively given, manner.

The latter was precisely the solution adopted by Ricardo, a highly unrealistic one, when it comes to the free wage-earner, but perfectly consistent with the commodity-status assumption. But Marx strongly criticized Ricardo on this issue, pointing out that the length and the intensity of the working day are variables determined by institutional factors.[6] All Marxian developments on the question of the “absolute surplus-value” are based upon this premise: the total labour time and its density (intensity) are fixed after the value of the labour power has itself been fixed.[7]

From the outset, namely his early above-mentioned writings, Marx boldly holds: human activity = commodity, and: wage = price of this commodity. As with all other commodities, there is a price and a value. The generality of the law of value is emphasized.

In the first book of CAPITAL, from Chapter VI to Chapter IX, he goes thoroughly into the same point. A perfect labour market is assumed and the wage (long-run, average wage) is perfectly determined by objective economic laws.

Then, all of a sudden, in the 10th chapter, we read that nothing at all has yet been determined, since, “apart from some limits, on the whole very elastic, the very nature of the exchange of commodities prescribes no limitation to the working day and to the surplus labour”.

What then determines the working day? To answer that question, Marx starts with a reference to the “general level of the civilization”, the “moral limits”, the “social and intellectual needs of the workers”, etc.[8] He ends by stating unambiguously: “The establishment of a normal working day is the result of a struggle of several centuries between the capitalist and the worker,”[9] Now, unless we resort to some highly artificial construction combining a determinate wage with an indeterminate wage rate, it is hard to realize how we can have a market daily wage rate when the length of the working day is the result of a political struggle.[10]

6) Any endogenous determination of the wage must previously solve the problem of an ex-ante homogenisation of the labour power. With the exception of some short sentences, here and there, about the extra cost of training of skilled workers, Marx did not keep his promise, formulated in the manuscript of 1859 to deal thoroughly with the “laws of the reduction” in a later work. Moreover, in the French translation of the first book of CAPITAL, supervised by Marx, a more or less substantial passage in chapter VII of the German text about the different complexities of the labour power has been eliminated in the French edition and replaced by a short sentence where an imprecise qualitative reference to “trades requiring a more difficult training” than others was substituted for the quantitative explicit terms of the original.

The disparity is too important to be imputed to the translator and seems to reflect some withdrawal of the author from his former unreserved belief in cost-of-production differentials determining value differentials of the labour power.

As a matter of fact, a “reduction” in relation to the costs of production would lead to results seriously diverging from the general practice of the capitalist world. As Henri Denis pointed out, the cost of production of a skilled labour power as compared to an unskilled one is mainly the part of the active life of the worker devoted to training on the one hand, to transmitting his skill to others on the other hand. For the whole society, the production of skilled labour is paid for with a proportionate shortening of the active life of the population.

If this wore so, the value of the labour power of a top engineer couldn’t exceed that of the simplest labour by more than or . This contrasts sharply with the actual span of wage rates which is many times larger than that. And not only is it larger statistically. It must be so theoretically. For, in the logic of the capitalist system, the man who devotes ten years of his active life to get a high qualification will not at all be content to receive for the remaining thirty years the same total amount that the unskilled labourer receives for his forty years active lifetime. He will at least claim a supplement compensating for the interests of the capital he spent (and/or failed to gain) during his studies, and, as in the capitalist system every capital, small or large, is entitled to a proportionate remuneration, he will get it.[11]

Here is where things go wrong. Because either the value itself of the labour power is charged with that supplement or the labour power is permanently and regularly (i.e. under equilibrium conditions) overpriced. In both cases the whole theory of labour-value is essentially impaired. In the first case, the value of the labour power cannot be determined without knowing the rate of profit (or the rate of interest). In the second, the rate of the surplus-value being the same whatever the qualification of the wage-earner, this supplement will be deducted from the surplus-value itself. Consequently, the rate of profit, instead of being determined by the rate of the surplus-value, would become one of its determinants. On the other hand, such a calculation would readily – as soon as we climb up the first few rungs of the qualification ladder – lead to a negative surplus-value.

The awareness of this deadlock is more and more gaining ground lately among Marxists, especially French speaking ones, such as Van de Velde , Henri Denis, Jacques Gouverneur (of Louvain), François Danjou, etc., the latter going so far as to energetically declaring that there is no way out unless we completely reject Marx’s idea, taken over from Ricardo, of scaling the values produced by different kinds of labour and recognize once for all that “the value produced by one-hour labour is one-hour value, be it supplied by a high grade white-collar or by a dustman.”[12] [13]

7) For the “value of the labour power” to be something more than empty words, we should be able (logically if not actually) to specify the bundle of the subsistence goods prior to their prices. But, what about if two subsistence goods, say wheat and potatoes, have the same physical “capacity” of producing labour power but different values? One would be tempted to reply that it is the one which has the smaller value that counts.That would mean that one takes the worker as being fed by his employer, like a horse or like a machine, with the most efficient ingredients in accordance with the very meaning of the notion of the “socially” necessary cost.

By letting the Department II appear in all his schemes, throughout his whole work, as a single process with a given unique set of technical conditions of production, Marx introduced a dangerous simplification. The output of this department ended by being dealt with like a composite commodity produced by a single industry with a given organic composition, and, therefore, quite homogeneous as regards value and price.[14]

Within such a framework the bundle of necessaries is exogenously, physically, given. Its value can be known prior to the prices and the problem we refer to simply does not exist. But in the real world the worker does not receive his wages in kind. He receives a certain purchasing power which he disposes of by choosing freely on the market his specific assortment. What is more important, he does not make this choice according to the relative values of the subsistence goods but according to their relative prices, Between the two relations there is a difference due, not only to market fluctuations which we can easily abstract from in theory, but also to the structural gap between values and prices of production, and this gap is influenced by changes in the distribution of income, namely by changes in the rate of profit. As, finally, the rate of profit itself is a decreasing function of the wage rate, the circle is complete. We run against the paradox that it is the wage which determines the value of the labour power (through the rate of profit and the prices of production of the subsistence goods) instead of the other way round. Incidentally, it is once again impossible to know the rate of exploitation without knowing the rate of profit.

A rather obscure passage in “Le Chapitre Inédit du Capital”[15] seems to reflect an awareness by Marx himself of some major internal contradiction impairing the concept of labour power as a mere commodity with a value established by its particular conditions of production.

“As a global price of every day average work, the wage contradicts the notion of value. Any price must indeed be reducible to a value, since the price – as such – is but the monetary expression of the value. The fact that actual prices are above or below their value does not make any difference. They are an expression quantitatively incongruous of the value of the commodity, even if in the particular case, the price is much too high or much too low. But in the case of the price of labour, the incongruity is qualitative.”(Emphasized by Marx)

The “incongruity” pointed out by Marx could already have been detected in the very division of the working day into paid and unpaid labour. Marx himself had previously, in the same work, recognized that “this expression is scarcely correct since it is not the labour as such that is sold and bought.”[16]

Marx does not say by what we could replace this “scarcely correct” expression. What is sold and bought is, to be sure, the labour power. But if, in the above sentence we replace “labour” by “labour power”, we would get an expression, not “scarcely correct”, but entirely incorrect, because, as a rule, there is no “unpaid labour power” and even when occasionally there is one, it is not this part of the working day which represents the bulk of surplus-value but what remains after the whole value of the labour power, paid and unpaid altogether, is deducted from the total labour time.

Now, Marx had already warned us when introducing his “moral and historical element” that the labour power differs on that account from all other commodities, but, apart of some disquietness transpiring in different parts of his work, he had never had the opportunity to examine the matter more closely and question frankly the theoretical consistency itself of submitting such a sui generis “commodity” to the general law of value and price governing by definition all commodities.

After all, when past labour is transformed into capital, every Marxist will agree that the latter is no longer a commodity but a social relation. Now, “social relation”, when it does not concern the simple social (human, sexual or whatever else) intercourse, either is empty words or it implies an economic issue (or “claim”) between rival economic agents. When referring to capital, the issue is the profit and the indispensable second half of this same social relation is labour power and wage. Then, the reasons are not clear why when the producer is transformed into wage-earner and the living labour into “labour power”, the latter should become a genuine commodity and could not remain a social relation too, just like capital and profit, land and rent, securities and interest, feudal rights and the “corvée” etc.[17]

8) But this undue dependence of “paid” and “unpaid” labour on prices occurs not only because of the ex post arbitration of the worker among available commodities, according to the variation of relative prices, but also because of the variation of the level of absolute prices according to the phases of the business cycle.

Marx has explicitly admitted the possibility of a fall of prices preventing the capitalist to realize in the circulation the surplus-value he has extorted in the sphere of production. Without further deepening this point, traditional Marxism tended towards distinguishing between created surplus-value, or unpaid labour, and realized surplus-value or profit.

What sort of thing, besides a mere potentiality, can a created but not realized surplus-value be, is not quite clear. But moreover, if the non-realization of the surplus-value is due to a general fall of prices, to the extent that this fall concerns directly or indirectly wage goods, the “surplus-value”, or whatever is “created” during the production, is refunded to the workers during the circulation, and speaking of unpaid labour is, in that case, completely meaningless.

It seems that the only way out of all the above shortcomings and contradictions is to give up any idea of determining the wage within the cost-of-production side, be it physical or social.

But this does not automatically rule out the possibility of an endogenous determination of the wage on the capitalist market by some economic mechanism other than the labour-value. All neo-classical theories, based either on the interplay of marginal utility of the wage and marginal disutility of human physical effort, or on the marginal product of the wage-earner, or on the prices obtained on the world market by the export sector (the latter determined in turn by the reciprocal elasticities of international supply and demand), do provide such an endogenous mechanism.

These theories have been repeatedly criticized and I do not intend to go through them again in this paper. There is, however, one endogenous explanation of the variation of the wages, which I shall try to discuss briefly, not only because it is interesting in itself, but also because, following some misunderstanding for which I probably am responsible, many of my critics found that it was closely related to my own position, some of them going so far as to think that I myself expressly agreed with it. I mean the theory of Arthur Lewis.

This author takes two countries which exchange the products of their industrial sector but not those of the subsistence sector. An unlimited flow of labour equalizes the earnings of that single factor in both sectors bringing those of the industrial sector down into line with those of the “immobile” food production. According to Lewis, it results therefrom that the productivity of the agriculture determines national wages. The country with the lowest productivity in the subsistence sector being by definition undeveloped, it follows that it is in the latter that the wages are lower.

There are two implicit assumptions without which the theorem collapses:

The first one is that the agricultural sector is governed not only by pre-capitalist but also by pre-commodity production relations, in such a way that it is not the monetary earnings but the physical yield in the backward food sector that regulates the wages of the advanced sector. In other words, the worker has the choice: either hire his labour power to the urban industry or till a piece of land and live on it.

Otherwise, the low productivity of food production in country B would drive not the industrial wages down, but the good prices up, as much as it would take to bring the agricultural wages up into line with those of the advanced sector, instead of the other way round.

The second assumption is that the land is free. Otherwise, some other revenue (e.g. rent) would siphon off the positive productivity differential of A’s advanced agriculture and nothing would be left for the benefit of the wage in that country,.

These two implicit assumptions, acceptable as they might, at the limit, be for the underdeveloped country, are completely unrealistic for the developed one. When combined with the explicit assumptions of the theorem, they transform the model into a mere school exercize. These explicit assumptions are: a) the international “immobility” of the subsistence goods, (obliging country B to keep its inefficient food sector going instead of specializing in rubber and importing food and steel from A), and, b) the assumption that labour is the only factor, (although our problem is the determination of the wages, that is, a variable implying the existence of at least two factors).

An agriculture which yields nothing more than the maintenance of the farmer himself is a very rare thing. It was the case in white-settler British colonies in the 18th and 19th centuries, where any citizen, discontent with urban wages, had the option to clear some unoccupied land and cultivate it for his own account, a situation which was focused on by several authors and which probably underlies Lewis’ starting point.[18]

Besides this case, we can find somewhere in the pre-capitalist communal structures, nearly the same situation (abstracting from various tributes extorted by external conquerors or bandits), albeit on the low side of the productivity scale. Supposing that some remnants of such relations are to be found nowadays, coexisting with an advanced capitalist sector, this would have a neutral influence upon the latter’s propensity to reduce the wages, since, whatever the wage, the communal man refuses absolutely to sell (or to hire) himself. In such a situation (which was quite frequent until recently in central Africa), the advanced sector could not help resorting to some coercion direct, or indirect with, as a consequence, the wage being fixed authoritatively by the same centre that exerted the coercitive action and as an integral part of it.

Thus, either the land is free and the worker is not “free” (for the capital), or the man is indeed at the disposal of the capital but the land (as the most important means of production) is not free, as it had to be taken away from the producer before the latter is transformed into wage-earner.[19]

Currently, agriculture yields considerably more than the equivalent of urban wage, contrary to what Lewis theorem suggests. An assortment of other revenues is, according to the circumstances, drawn from its product. Tithes, share-cropping proceeds, land taxes, usurious interests, excess profits or markups, etc.[20] The experience of industrial countries shows that it is not urban wages which are brought up into line with farmer’s earnings, after the latter have been increased by the rising of productivity – it is rather the rural exploitation incomes (i.e. others than those of labour) which are forced down by the intervention of the State in order to let farmers’ earnings follow at some distance the wages of urban workers, the latter having been previously raised by trade-union action.

Exogenous Determination of the Wage

As a cost input, the price of labour power, whether ultimately determined by its own “value” (rooted in the conditions of production), or just springing out of everyday immediate market forces, was likely to be formed through the market. Within this framework, could indeed the determinations be endogenous.

I believe that all attempts to discover such determinations have so far failed. There has indeed never been such a thing as a market for “free” labour – except perhaps a very short period following the establishment of the capitalist system. The complex code of rules and norms of the feudal system proceeding this period, the class struggle following it, left very little room for such a market.[21]

Paradoxically, as long as the worker himself was not free, there existed a real labour-power market under the form of the slave-market. It seems to have been the only one so far deserving the description of “market”. The Roman law had thoroughly clarified the matter by emphatically defining the slave as a res. The Marxian schemes as well as the preliminary ones of Sraffa, with their predetermined physically specified ingredients (output of department II In Marx, given commodities producing commodities in Sraffa), suit better that “pre-capitalist” situation than the capitalist relations for which they were conceived. For, as soon as the worker became “free”, the labour power ceased to be a “freely” traded commodity.

If this is so, the only possible solution is to take the wage for what it really is, viz., a direct distribution-variable reflecting each time and in each country an equilibrium point of antagonistic social forces.

In that case, determinations can only be exogenous and the question arises: what exactly within the distribution network is to be taken as exogenously ’given’? In other words, what is the independent variable?

The rates of surplus-value as the independent variable

Before going through the concrete elements of the distribution (real or nominal wage, rate of profit etc.) as possible “independent variables”, I would refer to the original and interesting attempt made by Henri Denis to reconcile the logical anteriority of the labour-value elements over the prices and the rate of profit with the acceptance of a direct determination of the distribution pattern. This consists in taking the rate of surplus-value as the ’given’ quantity (independent variable). It enables him to integrate the elasticities of the demand of workers and capitalists and escape from the deadlock of unspecified necessaries, letting the money wage, the rate of profit, the quantities consumed and produced and the prices be simultaneously determined, in such a way as to be consistent with the predetermined rate of surplus-value.[22]

We have here a handy solution and probably the only one capable of removing internal theoretical contradictions – surely, the anteriority of surplus-value is preserved, if we just take it as the independent variable. But the whole achievement is made possible thanks to two highly artificial assumptions. First, instead of deriving the value of the labour power from the use-values consumed by the worker, Denis derives the latter from the former, in conjunction with given elasticities of the demand and technical conditions of production. Second, he takes as the immediate object of the bargain between capitalists and workers, a magnitude as abstract and as remote from the usual terms of that bargain as the rate of surplus-value.[23]

The rate of profit as the independent variable

The most primary distribution ratio is the one between labour income on the one hand and remunerations of all other factors on the other. (According to British fiscal terminology, “earned” and “unearned” income). This is mainly fought out between the active capitalist and the wage-earner. All other incomes, rent, interest etc., are constituted within a secondary distribution process opposing mainly various sub-groups of the dominant class against each other.

For the sake of simplification, those who accept the necessity of placing the independent variable in the field of distribution generally amalgamate all non-labour incomes under the heading of profit. The problem is thus reduced to a choice between the rate of wage and the rate of profit.

Now, the wage can be real or nominal (money wage). As a matter of fact, actual wage is always nominal; “real” wage is just a concept. When it comes to a quantitative analysis, under conditions of a certain differentiation of consumer goods, one readily discovers that this concept is meaningless and useless.

There remains on the agenda however the choice between nominal wage and rate of profit and this is where the various positions move apart.

First of all, what is to be noticed is some general disinclination among scholars to take the money wage as the independent variable, irrespective of whether the latter is a physical quantity of the numéraire-commodity (convertible currency), or just a unit of account (inconvertible currency).

When reading related texts one wonders to what extent this discarding is deliberate and to what extent unconscious. Sraffa justifies this shift, occurring in his 6th chapter, from the rate of wage to the rate of profit, merely by pointing at the disadvantages of the real-wage alternative, without in the least mentioning the possibility of choosing the money wage, just as if this did not exist at all.[24]

Delarue merely observes that selecting the wage “necessitates first choosing a unit, whereas “r” is a pure number”, and continues his analysis with the latter taken as the independent variable.

When it comes to giving some positive indications of the particular conditions of such an exogenous determination of the rate of profit, Delarue is silent; Sraffa gives but a hint towards a possible determination by money rates of interest and passes on.

What is this money rate of interest capable of determining the rate of profit from “outside the system of production”, as Sraffa puts it? Are we to understand that the rate of profit is identical to the rate of interest and thus let the neoclassical model which had been expelled by the door creep back through the window? Sraffa does not care to answer this sort of question – yet the incompleteness of his explanation does not seem to bother too many people so far.

Finally, it seems that the decisive reason for which Sraffa as well as Delarue, and others, select the rate of profit as the ’given’ magnitude is that ’r’ is intrinsically independent of prices, being a pure ratio by nature.

This solution seems to me unacceptable for the following reasons:

1) In the real world profit is a residue and an ex post revenue. Consequently, there is no possible ex ante determination of its rate. What the workers negotiate is neither ratios and “pure numbers” nor the sharing of the national income between the capitalists and themselves in relative terms. They negotiate their own remuneration in absolute monetary terms.

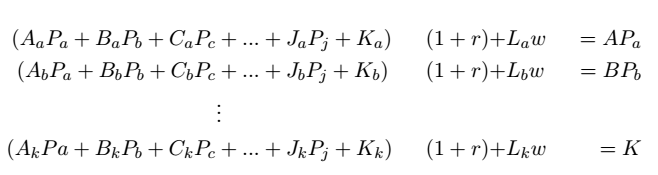

2) Taking the rate of profit as the independent variable implies that the famous “reduction” problem is assumed as solved, so as to have only one unknown, w, for one unit of abstract simple labour. That means that for k equations we have k-1 price ratios, a unique w and a unique r, providing only one degree of liberty.

Considering “r” as known, there remains k-1+1=k unknowns for k equations and our system is perfectly determined.

Now, as I have explained above, the “reduction” problem is actually far from having been solved and we have indeed more than one w, irreducible to one another.

It follows that the system is indeterminate, having more than k unknowns (k-1 price ratios plus more than one w) for k equations.

3) Particularly, in the field of international value, the path of an exogenous rate of profit is extremely perilous. Within the framework of a national economy, a unique ’r’ reflects adequately the relation of political forces, since this relation is established, not in each industry separately, but on the scale of the nation. But when we pass into the international framework and we assume an equalization of the rate of profit (as Delarue, Oscar Braun, Somaini and others do), it is not clear how a unique ’r’ could reflect throughout the world the multiple force relations, pertaining to each individual national reality. This difficulty compels the above scholars to take all ratios between national wages, wa/wb,wa/wc,…,wa/wk, as also given, and to leave only one wage, possibly the basic subsistence wage, as an unknown to be endogenously determined.

The result is that following an autonomous variation of the rate of profit, all wages of all countries will vary inversely to this rate but jointly and proportionately to each other, since they are linked together by predetermined ratios. This is, of course as comforting politically as absurd economically. Politically comforting because it ensures the absolute and ideal solidarity of the international proletariat. (If wa/wb is given, nothing, of course, can affect the one without affecting the other in the same direction and in strict proportion – one cannot indeed dream of a more perfect, mathematical, solidarity than that). Economically absurd, because it implies that the distribution of income is negotiated at two stages: a primary distribution between the entire capitalist class and the entire working class of the whole world, fixing respective global shares, and a secondary distribution between the working classes of each nation fixing their respective sub-shares in the pre-determined world wage fund.

Such a standpoint is unacceptable. The distribution of income in terms of profit and wages is immediately and directly a national affair. It is only indirectly that it becomes an international one.

If profits are subject to international equalization, the only magnitude which remains to be fixed by the national social struggle for the distribution of income is the national wage, in absolute terms. Each one of these national wages reflects the particular relation of social forces within the national framework. As such, they are independent of each other.

There is no reason whatsoever that a rise of wages in Germany, following local favourable political and social circumstances, should affect in either way, and even less so in a positive way, the nominal wage in Africa or in Latin America. If it affects something, it will affect the real income of African and Latin American workers, to the extent that they consume German goods, but then, on the contrary, it affects it in the opposite direction as I have already had the opportunity to stress, and far from establishing a solidarity, it gives rise to an antinomy of interests between the two groups.

Exogenous money wage

It is now possible to see more clearly the reasons that induce the taking of the money wage as the exogenous variable, being well understood that we have as many autonomous exogenous variables as there are different national rates, plus the hierarchical differentials within the nations.

But then the question arises: how can a wage expressed in money terms be an exogenous, independent variable, since its real contents depend on prices and prices themselves depend on the rate of the wage?

In other words: in order to be able to determine relative prices, the distribution of income should be known prior to them; but what meaning has a distribution in money terms without an already given set of relative prices?

How can social classes fight out a nominal money wage? What do a hundred pounds or a hundred dollars mean ex ante in real terms, even when they represent physical quantities of the numéraire-commodity in a perfectly convertible monetary system? (If they are only bank money, their significance will be even more questionable.)

Everybody will understand that this question goes beyond the point. If somewhere, on the earth or on another planet, men exist who are so foolish as to struggle for bits of paper or for pieces of a particular metal, instead of struggling for steaks and clothes – despite the fact that the relation between the former and the latter depends itself on the quantity of the bits of paper or of the pieces of metal each one of them will receive – the theory should nonetheless be able to account for this happening, and mathematics – universal and neutral language – should be able to put it into formulas, independently of the possible explanations of such “irrational” behaviour.

Now, it is an established fact that people do bargain and struggle in terms of these “valueless” things and that wage-earners do resist more a nominal reduction of their earnings than an equivalent increase of prices. These doings are inconsistent with theories which postulate that a given force relation equilibrates at a given rate of surplus-value or at a given rate of profit. For the behaviour of the nominally minded protagonists make it possible that for a given relation of social forces there are more than one rate of surplus-value and of profit.

The fall of the real revenue of the worker during the great discoveries of new silver and gold mines in past centuries would be unexplainable with these theories because the rate of surplus-value or of profit should then depend on the conditions of production of the numéraire-commodity, which is absurd.

But workers and capitalists are not so foolish. If a hundred pounds or a hundred dollars mean nothing ex ante as regards the real consumption of the worker, one hundred and ten units of a currency whatsoever represent, in physical terms and independently of the prices, a purchasing power superior to the one represented by only a hundred units of the same currency.

Can we compare independently of the prices two purchasing powers which consist of two collections of heterogenous goods? We can – because the price system is such that, all other things being equal, no price varies more than the wage variation which makes it vary.

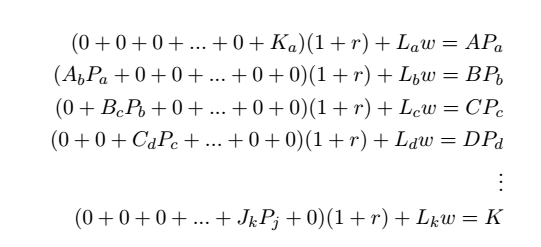

Let us write down a system of relative prices:

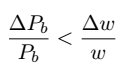

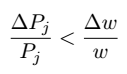

What we have to demonstrate is that

All elements of the input matrix on the left must be either positive or nil. However, it is clear that in each process-equation there must be at least one element, other than the output of the same process, which is non-nil. Otherwise our system is being dismantled into several perfectly determined sub-systems. This constraint expresses on the mathematical level the Sraffaian condition demanding that all outputs be basic commodities, that is, each one of them must enter directly or indirectly as an input into all other processes, consequently directly into at least one of the other processes.

Therefore there is an elementary (minimal) diagonal matrix which must be contained within any combination, the rest of the elements of the combination being indifferently positive or nil:

Following a variation of w, remains unchanged and r varies in the opposite direction. Hence:

which entails

which entails

Obviously this result will be not affected by filling up the matrix by as many positive inputs as we like, since each one of them varies less than w.

Now if no price varies (e.g. rises) more than the price of the wage which provoked its rise, it follows that the recipient of this rise, for example, from a hundred monetary units to a hundred and ten, can, if he so wishes, obtain from each one of the items of his consumption assortment more than what he obtained before, provided he refrains in each item from going beyond a certain particular limit. If the elasticities of his demand are such that he wants to go beyond these limits in some of the components of the assortments, he will be obliged to accept a reduction in the others. But in that case the new assortment will be superior to the previous one owing to this very choice.

Suppose we have two commodities a and b, and that with 100 money the consumption of our man is ![]() . The price system is such that with 110 money he will be able to consume

. The price system is such that with 110 money he will be able to consume ![]() where

where ![]() and

and ![]() and consequently,

and consequently, ![]() .

.

If instead of ![]() , he prefers

, he prefers ![]() , where

, where ![]() but

but ![]() , then

, then ![]() by virtue of this preference and as

by virtue of this preference and as

![]()

it follows that![]()

This is what gives meaning to the bargaining in money terms prior to prices.

In some way there is a trial and error process, each bargaining process attempting to compensate the gap between real variation and nominal variation stemming from the previous bargaining process.

Now, being given that the issue here is a general increase in the wages, the general price index will not vary and being also given that the range of wage goods is sufficiently large for the positive and negative differentials to compensate for each other, the structure of the wage goods assortment is likely to be nearly identical to the structure of the whole social assortment and so the difference between volume and value, if any, will be father insignificant. Anyhow this difference – over or under the expectations – will affect the bargaining position of respective parties at the next negotiation and so on.

From this point on, any wage theory will necessarily be confined to exploring the exogenous determination of the remuneration (price) of the worker (labour power). It will necessarily have to analyze the complex interaction process constituted by, first, the evaluation of the relation of social forces within the limits of the level of development of productive forces; second, the direct influence of the variations of the wage on the movement (forward or backward) of the same limits, and, third, the feed-back effects (positive or negative) of the development of the productive forces on the bargaining power of the parties and consequently on the equilibrium point of the force relation at each point of time.

Sussex 2.11.1975.

- Marx himself admits that the only deficiency of Classical Political Economy was “its failure to show how this exchange of a greater quantity of living labour against a smaller quantity of materialized labour did not contradict the law of the exchange of commodities, that is, the determination of the value of the commodity by the labour time; …” (“Chapitre Inedit du Capital”, pp. 174-175).(Many of my references are made to French editions and corresponding quotations have been translated by myself from these editions. Unfortunately, I had not enough time, during the drafting of this paper, to look for respective English editions. I apologize for any inconvenience this inadequacy may cause the reader). ↑

- Since, on the other hand, nothing prevents the value of its components, the goods consumed by the worker, to undergo this transformation, we have there an output in value terms while its inputs are expressed in price-of-production terms, an anomaly which will raise some awkward problems as we shall see later on. ↑

- cf. also Plekhanov, “The Socialism and the Political Struggle”: “A certain wage is the effect of the level of the vital needs of the worker, but these needs cannot increase without a rise of the wage. So the wage becomes the cause of a certain level of the needs.” ↑

- cf. “Value, Price and Profit”. Also CAPITAL, B. I., sec. sect. Chapt. VI. ↑

- Rosa Luxembourg realizes that this “traditional standard of living” can only be enforced by trade union action and by some sort of automatic cultural diffusion, but she does not seem for all that to suspect the implications of such an admission as regards the operation of the law of value. (cf. “Social Reform or Revolution”). ↑

- So far as I am aware, Marx did not deal explicitly with the length of the active life. But it is clear, at least in the modern states, that this is even more institutional than the length of the working day, in as much as it is dependent on the length of compulsory schooling, retirement devices etc. ↑

- Otherwise there is no room at all for the very concept of “absolute surplus-value”. ↑

- Some kind of inversion between cause and effect seems to occur here. We would rather say that it is the length of the working day which determines the cultural activities of the worker than the other way round. ↑

- CAPITAL, B. I., sect. Capt. X. ↑

- It should be underlined that this explicit “hooking” of the working day to extra-economic factors is not made by Marx as an allowance for objective impurities lying outside the theoretical space, but as part and parcel of the theory itself, since it constitutes the starting point of the distinction between absolute and relative surplus-value.How can such an hybrid construction be explained? I think that this is a good example of what I would describe as the ontological side of Marx’s work transpiring particularly in some passages of the first book of CAPITAL. The end result of such a position will be that the value becomes a real being transcending the market and permeating the commodity. Market mechanisms, namely the mobility of the independent producers, as a necessary condition of commodities exchanging at their values, slide out of sight. As a consequence, the lack of such mechanisms becomes immaterial.Another example of such a metaphysical treatment of the concept of value is constituted by the theory of absolute rent, the falsity or the weakness of which very few Marxists deny to-day, and according to which the agricultural product sells at its value, just because the conditions of its exchange at its price of production are missing.A third example is the equalization of the rate of surplus-value in all industries. The whole work of Marx is grounded on this crucial and, to be sure, thoroughly legitimate assumption. It is however remarkable that in a work as systematic and as voluminous as the first book of CAPITAL, where no detail is neglected where hundreds of pages are devoted to the theory of the surplus-value, there is not a single word to justify an assumption as fundamental as this equality. So much so that Seton and Morishima (overlooking a very short statement of Marx, lost somewhere in the middle of the Third Book within a quite different context, which justifies this assumption by the mobility of the workers), concluded that this postulate must be “regarded as a hidden part of the definition of ’value’ rather than an independent postulate that could be changed at will”. (Econometrica, April 1961). ↑

- Serge Latouche, “Le Projet Marxiste…”, Paris 1975, pp.84-86, reports that some research carried out in the United States indicates that the real hierarchical gap is considerably larger than that. ↑

- Given that “negative surplus-value” simply means that, instead of supplying surplus value, the worker is appropriating some of it which was produced and expropriated elsewhere, it is noteworthy that, while admitting that possibility with, wage gaps ranging over 1-2 or 1-3 and despite the differences of qualification, when it comes to wage gaps of 1-20 or 1-38 and for the same qualification these authors are considerably more reluctant to allow for the same possibility, just because the gaps occur now between countries, instead of within the boundaries of the same country. ↑

- Another interesting objection is raised by Danjou: Does the “complex” labour receive a higher wage because the cost of its maintenance is higher or is it because the wage is higher that the complex labour can afford to be maintained at a higher level? The “cost of reproduction” of the labour power is more a cost of reproduction of the social hierarchy than a cost of reproduction of the skill. ↑

- In some degree, Marx himself seems to have been lured into the trap. So in some places, for instance in the Grundrisse, he puts the subsistence goods literally in the singular: “…the wages are therefore measured by a given use-value and as the value-of-exchange of this is changing according to the variations of the productivity of labour, the wage or the value of labour is changing too.”But this is only an indirect hint. There is a direct one. We know that Marx’s theorem, taken over from Ricardo, namely that a variation of wages would entail a variation of the same sign of the prices of production in the industries whose organic composition is lower than the social average and an opposite variation in the others, is false as soon as the simplification of a single process for all means of production and a single process for all subsistence goods is dropped. It is then plausible to suppose that Marx had simply forgotten to drop it and had led astray by his own oversimplified construction. ↑

- p. 284 ↑

- p. 80 idem. ↑

- However, in the work mentioned above, Marx wrote: “Capital and wage-earning labour are two factors of one and the same relation.” (p. 168 of “Le Chapitre Inédit du Capital”).Symmetrically, capital, in its turn, can be fetishized and visualized as a concrete object. So, the §C of the same work, dealing with the variations of the surplus-value, is headed: “DETERMINATION OF THE PRICE OF THE COMMODITY CAPITAL” (idem p. 100) ↑

- cf. Wakefield’s project in CAPITAL, Book I, Chapt. XXXIII, Bakounine, “Fédéralisme, Socialisme et Antithéologisme”, Oeuvres I, p. 29; also, Ch. Bettelheim, “Le Problème de 1’ Emploi”, Paris 1952. ↑

- Curiously, it is among Marxist economists, who, by definition should be the most sensitive about this separation of the producer from his means of production – a precondition of the establishment of the capitalist mode of production – that one can find the most responsive audit of Lewis’ model, built on the assumption of an open land, free of charge to the producer. “The first condition” says Marx, “of capitalist production is that the ownership of the land has already been snatched out of the hands of the people.” Capital, Book I, Chapt. XXXIII.It follows that making the level of wage depend on the productivity of the land is meaningless. When the land is free the wage system is not a dominant social relation and when this is dominant the capitalist rent sponges away productivity differentials, not allowing them to pass on to the wages. ↑

- “However rough the subsistence supplied by Ilots to the Spartans might be, it is certain that, if the soil of Sparta yielded no more than what was necessary to sustain its labourers, Spartans would either have perished or been obliged to dismiss their slaves and cultivate their lands themselves.” Quesnay: The Rural Philosophy, Chapt. VII. ↑

- Even in this transition period the existence of a real labour market is very doubtful. Cf. E.S. FURNISS, “The Position of the Labourer in a System of Nationalism”: “…it is necessary that we bear in mind that the rates of wages actually paid in England at the time were supposedly determined by the Justices’ Assessments, and that, though the rating of wages had in large measure been allowed to die out, preceding centuries of more or less rigid wage regulation had prepared the common mind for an uncriticizing acceptance of the opinion that the income of the labouring classes must be governed by state action…in regard to wages no champion of the laissez-faire policy appeared; the interest of the dominant classes remained on regulation, and the writers of the time continued to exhibit the habit of mind formed when the rating of wages was a matter of course.” pp. 157-159. ↑

- cf. Working Papers, IREP, Grenoble, N°4, May 1972 and N°5, Sept. 1972. ↑

- One of the reasons set forth by Sraffa for not taking as the independent variable a wage expressed in terms of the standard commodity is that it would be too abstract to have a definite meaning. ↑

- (While the real wage has no meaning until the prices are determined)”…the rate of profit, as a ratio, has a significance which is independent of any prices and can well be ’given’ before the prices are fixed.” (Production of Commodities by means of Commodities, Cambridge 1963, p.35).It can indeed! And real wage cannot. But what has been lost sight of is that nominal wage can also be given, and not only it can; but, what is more, is actually given prior to prices in everyday practice. ↑