Download as PDF.

Between the consolidation of the Bolshevik revolution, in the 1920s, and the end of the last war, or, more precisely, the time when polycentrism became a reality, Marxist theory passed through a period of hibernation.

Basically, the main concern of revolutionary Marxism was in this period completely identified with the struggle for survival than being waged by the first model of socialism. The development of Marxist theory became the exclusive business of one political party and its own fringe of dissidents. In those days the only conceivable non-Stalinist Marxists were the Trotskyists.

Given that situation, a West-European publishing house could hardly risk investing in a translation of the works of Rosa Luxemburg or of the Populists. Both Stalinists and Trotskyists would have seen it as the most way-out of intellectual activities to read more of those writers than what Lenin and the Leninists had quoted in the course of refuting them.

The sudden awareness that the Soviet Union and the other countries of “actually existing socialism” could not, or could no longer, serve as a model and, more especially, that their survival as Communist states had not de-stabilised Western capitalism, or even affected its subsequent development, caused a shock which spoilt all those certanities. There followed a lively questioning of all accepted ideas. A sort of generalised iconoclastic release of inhibitions replaced the devout orthodoxy of the previous period. This explosion produced some positive effects, advancing and enriching Marxist theory, but also a lot of shallow verbiage and some harmful theoretical skids. This paper offers a rapid survey of the latter.

A decadent neo-rationalism

First of all there appeared those phenomena which are typical of periods of “decadence”, with its most characteristic symptom, namely, flight from an inconvenient reality. Marxist intellectuals turned in on themselves, seeking refuge in the holy-of-holies of the “concept”, wherein they could discover, at leisure, in an imaginary world, the solutions that the real world refused them.

Thus, the fundamental principle of historical materialism, the primary of being over consciousness, was completely rejected. On the pretext that man cannot apprehend reality except by re-creating it in thought, the “object of thought” ceased to be an instrument for the cognition of truth and became, instead, the creator of reality. A certain Bergsonism present in Gramsci, a voluntarist aspect of Lenin, and the vestiges of the Hegelianism of his youth to be found in Marx served as base for all those who lacked the patience to wait, before overthrowing capitalist society, until “all the productive forces for which it is sufficient have been developed.”

This neo-rationalism gets stuck in contradictions. That phenomena, as Varagnac puts it, do not by themselves coagulate into intelligible masses, that regroupings and “causal connexions” have to be effected by the mind, and that theories alone can bring about such transmutation, nobody can deny. That the concept is therefore a “tool for cognition produced by thought itself” (C.Dumenil) is also undeniable. That apprehension of reality by means of “concrete thought” is different from mere abstraction can also be agreed. But if metaphysical parthenogenesis be ruled out, it is not clear how the production of this tool itself could take place without a somehow original (unconscious?) preliminary abstraction from particulars. Even if inadequate as the instrument of “cognition”, abstraction would seem, then, to be adequate as the instrument of the instrument.

But particularity is not found upstream only. It is there downstream as well, in the capacity of ultimate test of truth. After all, in order to “apprehend reality” the paranoiac, it has been said, uses exactly the same mechanism as is used by the person of sound mind. Besides, “concrete thoughts” such as ether and phlogiston were constructed (and, in these cases, by men of sound mind) in accordance with the same procedure as any other concept in physics. What differentiates them? To discover that, we have no other criterion than the verification, and, above all, the denial which is supplied, or inflicted, by the phenomenon.

Although un-knowable without theory, the phenomenon is thus itself the only criterion of the validity of theories. The contradictin here is merely apparent. For the phenomenon does not need to be “known” (in the full sense of the word) in order to serve as touchstone of “knowledge”: it is enough for it to be “recognised” as existing. While we need a theoretician and maker of concepts in order to “know” rain, the least educated peasant is capable of “recognising” it. No doubt one has to be a doctor in order to give meaning to “heart failure” and conceive one or other of the two forms of treatment at present offered for this condition, namely, surgery or chemotherapy. But when these two methods have been applied long enough for the appropriate “large number” to reached, then, in the end, it will be a commonplace statistic of comparative mortality that will decide between these two schools, which are made up of scientists of comparable quality and equipped with theories of equal intrinsic solidity. Thus, it is theory that makes the phenomenon an object of cognition but it is the phenomenon itself – not known, crude, merely perceived – which gives sanction to theory. Refutation and denial are often confused. Theory alone “refutes”: the phenomenon can only “deny”. But the theory of today exists only by and thanks to a denial suffered by the theory of yesterday.

Theory of value and theory of prices

On another plane, but proceeding from the same unconscious motivation, namely, to escape from the world of the practicable to that of the desirable, a tendency has appeared which blames certain impasse experienced by Marxist economics either upon a too positivist reading of the texts or upon an empiricist evolution in Marx’s own thought, between the Grundrisse and Volume Three of Capital.[1]

According to this tendency, Marx’s actual plan was not to criticise classical political economy from within, and so to “continue and perfect” it, as Lenin claimed, but rather to reject it per se.

This means seeing political economy more or less in the same light as a non- believer has to see theology. He does not discuss theological questions, he questions the validity of theology. Thus, from this standpoint, we have, on the one hand, economic analysis in general and, on the other, Marxist analysis in general, just as there is the religious view of the world and the materialist view of the world, and a “Marxist” economics” would be a contradiction in terms as blatant as an “atheist theology.”

It is on the level of the theory of value and of relative prices (prices of production) that controversy grows lively. Political economy is, par excellence the science of the quantitative. The transformation of qualities (use-values) into quantities (exchange-values) is its prime object. However, the “neo-Marxists” we are dealing with aspire to raise themselves above the vulgar quantitative. Explaining exchanges is all right for little Sraffa. He does it very well. But the great Marx cannot be an “economist”! When, by mistake, Marx ventures in that direction, he suffers defeat. “His giant’s wings prevent him from walking…” The theory of value has a much nobler function – to explain how the commodity originated and to demonstrate exploitation.

Very well. But when they say this, the Marxists in question lose sight of one thing. There is no way in which one can form a theory of the commodity, and so explain the transformation of use-values into exchange-values, without concerning oneself with exchanges themselves and without indicating what determines them and measures them and it is likewise impossible, in a market economy, to demonstrate exploitation without regard to the market.

For it is not a matter of stating the simple possibility of quantification — of saying, for example, that, given certain abstractions and reductions, a hat and a chair become commensurable. Given certain abstractions and reductions, an eclipse of the sun becomes commensurable with a whisky-and-soda. Consequently, if we confine ourselves to showing the simple possibility, in itself, that there may be some equivalence between the various things that reproduce life and human society, we avoid all contradictions; but we also reconcile Marx and Jevons, and we move not a single inch forward on the road to knowledge.

If we rest satisfied with noting the simple fact of commensurability, while adding thereto the idea that this fact implies the existence of a common element we say something which is irrefutable and universally true, but which is also tritely tautological. “Universal truths” are, indeed, irrefutable only in so far as they are tautologies.

But if we claim to specify what this common element is, we can no longer get away with disdaining particularties and so transcending political economy. For nothing guarantees a priori that there are not several common elements and, if that is so, no pure reason can show us which of them is the right one, that is, the one which serves effectively and positively as the factor of commensurability in the particular case that concerns us.

That abstract labour could be a common substance in relation to which goods quantify themselves – well, really: “Abstract need” would fill the same role precisely, with the same difficulties of transition from the concrete to the abstract. There are even common substances that would do the job still better: weight, carbon-content, and so on. It is therefore not enough to name a common substance and show that it exists: we have to prove that it is the right one. And the only way to do that is to analyse exchanges and show, if not statistically then at least logically, that they could not continue if they were systematically to deviate from the measure provided by the “substance” whose cause we advocate. We must, consequently, before ascending to our Olympus, pass through the valley and dispose of Jevons and some others on their own ground. Because the only thing that constitutes a foundation for the idea that labour is not just one but the common determining “substance” is, precisely, that when we relate it to exchanges, it emerges as their only possible measure. On the other hand, if one were to take the line that this is merely a simple mental construct and that, “positively”, exchanges never align themselves in that ways even when r = 0, even when c is proportional to v, then one would have no means of justifying one’s choice.

Consequently, a theory of value is indissociable from and implies a corresponding theory of prices.

It is precisely by his thesis of the transitory (and not immanent) nature of value that Marx distinguishes himself from Ricardo. He shows (very positively and very empirically) that it is only under certain historical conditions that some useful objects, having been appropriated by independent producers and become reproducible at will, are transformed into commodities. It is then and only then that the labour socially necessary for the reproduction of each of these objects becomes determinant, as the common element in them. There is transition from simple “exchange equation” to “economic equivalence” (John Rettel). In other terms, there is transition from a situation wherein we write, ex post, “1 of wheat = 2 of iron,” because that is, in fact, the rate at which they are exchanged, to a situation wherein 1 of wheat is exchanged (tends to be exchanged) for 2 of iron because 1 of wheat = 2 of iron ex ante.

But from that moment the reciprocal contract of exchange is no longer of the “do ut des” type, as it was, objectively, when the only determining factor was the need of the moment, and as it always is, subjectively the minds of those making the exchange. It now belongs to the “facio ut facias” type. This is what makes all the difference. Under the appearance of an exchange of things is hidden the reality of an exchange of labours.

Let us take the extreme case under simple commodity relations: infinite divisibility, passage from one branch to another regardless of time, perfectly continuous flow of production, and apprenticeship proportional to the quantity produced – and, finally, the means of production at the disposal of those who use them (so that r = 0).

Given these conditions it is quite obvious that, if it takes 15 minutes, without apprenticeship, to produce a tomato, and 20 minutes, plus an apprenticeship of ten minutes to produce a poem, I shall never agree to give more than two tomatoes for a poem, no matter how great my desire for the poem and my distaste for tomatoes. I shall resolutely reject a proposal that I hand over three tomatoes in return for a poem, since, by working 30 minutes — ten for the apprenticeship and 20 for the writing – I can myself create the poem I want; whereas, to replace in my shop-window the three tomatoes asked of me, I should have to work 45 minutes. For the same reasons, the owner of the poem will not exchange it for fewer than two tomatoes.

Clearly, this does not happen when my child exchanges his lead soldiers for marbles, or when persons on a desert island exchange tins of food made available to them through a wreck, or when calf’s liver is exchanged for veal in white sauce. In these three cases the objects exchanged exist, or are reproduced, in proportions which are independent of the actions of the persons making the exchanges: in the first case, through the chance of presents received; in the second, Fabs the caprice of the waves; and in the third, owning to a biological constraint. The exchanges here belong to the “do ut des” type, and the neo-classical analysis is perfectly applicable to them.

But, should my child happen to learn that the factory which makes the two kinds of toy accepts their return, and exchanges them one for another, it is quite obvious that, whatever his preference-curves and the state of his stock, he will not agree to a rate of exchange which is less to his advantage than that offered by the factory. Similarly, if our Robinson Crusoes come into contact one day with an inhabited region where all the different kinds of tinned food they possess are being made, they will start to take as their standard, in their own exchanges, the price-relations which prevail in that region. And it would be the same if, one day, somebody were to invent a means of producing at will (but at different costs) calves in white sauce and without livers and calves with livers and without white sauce.

Under the specific conditions of commodity relations, the true content of exchange, that which happens “behind the back” of the persons exchanging, and unknown to them, is not: I give you two tomatoes and, in exchange, you give me a poem — “do ut des”. It is, rather: I am going to cultivate the soil for half an hour for you (or somebody else is going to do it on my behalf) and, in exchange, you are going to write verses for me for 20 minutes (or somebody will do it on your behalf)– “facio ut facias”.

The fact that “do ut des” is situated in the present, whereas “facio ut facias” is necessarily projected into the future, far from vitiating this presentation, shows, on the contrary, that it is the only one compatible with Marx’s labour- value, since Marx emphasised many times that it is not the labour actually expended in the production of a commodity that counts, but the labour necessary for its re-production.

From the time of that historical mutation of d̈o ut des̈ into f̈acio ut facias,̈ the problem to be solved is no longer the commensurability between tomatoes and poems, but that between horticulture and versification. This is why we need a “practical abstraction,” to use John Rettel’s formulation. For my part, I should say, rather, that we need a certain preliminary practice is in order to render the mind capable of affecting the abstraction in question. This practice has the result that we attain such a degree of social indifference (mobility) as between the different forms of labour that it becomes possible to extract from them the concept of “more labour.” But this is always an abstraction. We proceed from the particular to the general, from being to consciousness: we do not descend from the general to the particular, to embody a concept in reality.

As for the explanation of exploitation by labour-value, the petitio principii is so flagrant that it is not worth talking about. Saying that the raison d’etre of the labour theory of value is not to explain exchanges but to demonstrate exploitation automatically deprives this theory of any capacity to do just that.

Absolute value/relative value. Production/circulation

If we locate the source of truth in the internal articulation of concepts, we are inevitably led, on the one hand,to a certain substaintialising of value, and, following there from, to the notion of absolute value, which contradicts the relativity of prices, and, on the other, to necessarily giving priority, in the total circuit of capital, to the immediate production-process phase, as against the circulation phase.

I

If, indeed, like the neo-rationalist Marxists, we think of value as a sort of jelly that runs from the veins and muscles of the worker to permeate the commodity, then its quantum is given us for each individual commodity, independently of all the rest – which is the definition of absolute value. Furthermore, the division of this jelly between the wage-earner and the capitalist can only take place in the factory and before any exchange. We thus arrive at the absurd notion of an exploitation the measure of which is independent of the distribution (or redistribution) effected through prices.

The impasse is complete when, subsequently, in constructing a theory of the prices known as “prices of production”, an attempt is made to ensure the survival of this “jelly”: in other words, when it is sought to present equilibrium prices as modified absolute values overlooking the fact that, anyway, values that can be modified by the action of a factor of distribution (equalisation of the rate of profit) can never and in no case, by definition, be absolute.

Let us take a simplified example. Suppose that our system produces only two commodities, A and B, and that it disposes of 600 hours of social labour, which are allocated half-and-half to each branch, but that the as (the matrix of the inputs) are such that when they are multiplied by a single (1+r), the rate of exchange is “transformed” from A/B = 1 into A/B = 2.

This latter rate exhausts the information we can derive from our equations, and it is, as such, as relative as anything can be. True, if we put this rate, A/B = 2, in correlation with A + B = 600 (total social labour), we get A=400 and B = 200. That looks pretty absolute. But, in the same way, we should have got A = 6 and B = 3 if the same rate A/B = 2, had been put in correlation with A + B = 9 kilowatt-hours (assuming that this is the total amount of electric power expended in the two branches of production). No more in this case than in the first one do the cardinal numbers (400, 200, 6, 3) have anything to do with the actual quantities, either of social labour or of electric power, incorporated in A and in B, the former being, in reality, 300,300, and the latter whatever like. Despite their absolute air, the equivalences A = 400, B = 200, or A = 6, B = 3, are only ways of saying that A is to B as 400 is to 200 (or that 6 is to 3) in the abstract – which is something as relative as anything can be.

Is it meaningful to say that the isolated price of production of A is equal to 400 hours of social labour? In itself, in absolute terms, it is meaningless. According to the data we have, to produce A we need not 400 but 300 hours of social labour (past and living labour together) and this fact cannot be “modified” in any way by the “transformation.” A = 400 has no meaning unless it is put in correlation with B = 200 (or with A + B = 600), so as to signify that, as a result of the equalisation of the rate of profit, A and B are exchanged (on the average and in the long run) as if the former necessitated 400 hours and the latter 200. It is clear that, formulated like this, the content of these equivalences is perfectly relative.

It follows that the equivalences shown above, A = 400 and B = = 200, are either absolute and insignificant or significant and relative. They cannot be both absolute and significant. In fact, absolute values, whether “modified” or not, can signify only if they are given before relative values, and determine them.

Yet at the moment when it is established by our “transformation” equations that A/B = 2, the initial absolute values (300, 300) are no longer there and the new, “modified” ones (400, 200) are not yet there. The latter do not arise until A+B = 600 is deliberately added, for no other reason than to obtain absolute values – that is, to meet the needs of our cause.

Giving A = 400 hours and B = 200 hours and deducing from this A = 2B, as is done at the level of Volume One of Capital, is not at all the same as giving A = 2B and A + B = 600 and deducing therefrom A = 400 and B = 200, as is attempted at the level of Volume Three. In the first case, we pass from (absolute) values to (relative) exchange-values: in the second we re-transform into absolute values a set of directly calculated relative prices. Whatever, then, may be the intrinsic merits of the absolutist thesis, the “transformed” values it puts forward are only pseudo-absolute.[2]

It could be objected that what is absolute is not A = 400 and B = 200, but A+B = 600. In so far as A + B = 600 expresses a reality which survives the “transformation”, its addition cannot be dismissed as question-begging.

“600 hours of total social labour” is indeed a magnitude that is both significant and absolute. The trouble is, it is not a “value”. It is a mere demographical fact. If I say that India’s annual product is equivalent to 480 milliard hours of abstract labour, whereas that of the United States is equivalent only to 176 milliard, I may imagine that I am saying something very profound, but, in fact, these figures represent merely the products of multiplication of the number of the active population in each case by the number of hours to be worked in one year.

This has nothing to do with a problem of “value”, whether this be absolute or relative, and whatever its conceptual framework — Marxist, neo-Ricardian or neo-classical.[3]

What is Marx’s own position on this point? It is true that some passages in his writings do imply, at least, an absolutist view of value. However, I think that these passages are contradicted by the rest of his work, and not just implicitly, either. There are passages which explicitly reject the idea of absolute value. Here is one of the most important of them:

“To estimate the value of A in B, A must have a value independent of the estimation of that value in B, and both must be equal to a third thing expressed in both of them. It is quite wrong to say that the value of a commodity is thereby transformed from something relative into something absolute. On the contrary, as a use-value, the commodity appears as something independent. On the other hand, as value it appears as something merely contingent… It is to such an extent relative that when the labour-time required for its reproduction changes, its value changes, although the labour-time really contained in the commodity has remained unaltered.” (Theories of Surplus-Value, Volume III, London, 1972, pp 128-129: Marx’s own emphases).

The relativist thesis can also be supported indirectly by all the passages in which Marx stresses the point that value is not a property of things but a relation between men, a social relation. This, indeed, is where Marx differs from Ricardo. The latter saw quite well that capitalist relations were only a later historical phase in the evolution of simple commodity relations — but he saw those relations as having existed from the earliest times. Marx showed that simple commodity relations themselves, and, consequently, the law of (non-transformed) value, also had a history. They were the corollary not of society as such but only of a certain type of society, and would disappear with it. One can hardly reconcile this historicity with the substantialism of those who see labour-value as a common property immanent in things exchanged.

Reciprocally, the fact that a price – and, therefore, an equivalence – can exist for things which are not true values, such as land, or some collectors’ pieces proves well enough that labour is not only possible element common to things exchanged.

It remains the case, however, that, when he went over from simple commodity relations (r = 0), or undeveloped capitalist relations (c negligible, or proportional to V), to developed capitalist relations ( = r and c/c’ =/= v/v’), Marx tried to show prices as determined by “transformed” values, which certainly does seem to proceed from an absolutist point of view. But this attempt of his is well known to have failed, and that defeat demonstrates precisely that it is not possible to maintain the principle of a common element, as physical and immanent (and therefore absolute) as the quantity of labour expended (measured in terms of time), in prices which are so relative as the “prices of production.”

The long discussions which have taken place recently around the problem known as “transformation”, and Sraffa’s solution to it, bring us to the unavoidable conclusion that it is not price of production that is a special case of labour- value, as Marx vainly tried to prove, but labour-value that is a special case of price of production, being the one in which r = 0 (or c is proportional to v) Actually, what is necessary and sufficient to provide a aingie solution, before the market, of the problem of relative equilibrium prices is a standard of allocation involving an internal equalising of the remunerations of each of the two factors by its own principle of reduction. In the special case where labour is the only factor, this equalising can be effected only if the commodities are exchanged in proportion to the quantities of labour needed to produce them. This creates the illusion that these are the quantities which directly determine the exchange-values – and hence we get the substantialist view of the matter. This illusion is disturbed as soon as a second factor is introduced into the system, because at that moment the exchange-values become visibly disconnected from the (physical) quantities of one or other of the factors. And so we get the present commotion.

Yet the singleness of the solution to the problem of prices is maintained. This alone should help us to understand that if, in the special case of the single factor, A was equivalent before exchange to 2B, that was not because A embodied four hours of labour, whereas B embodied only two (even if that was actually the case), but because the person who had worked four hours demanded, and through the law of competition obtained, twice as much of the social product as the person who had worked only two hours (facio ut facias). When the factor of capital comes into play, it turns out that A is no longer equivalent to 2 B but let us say, to 3B. It then becomes clear that it is not because A required three times as much labour as B that A = = 3B (since this is not even the case any more), but because it is at this rate, and at this rate only, that equalising of wages, on the one hand, and equalising of profits, on the other, is found to occur.

II

Proceeding from the same substantialist standpoint, some are heard to proclaim, loud and clear, that it is the production phase that determines the phase of circulation and distribution. Actually, apart from the tautological and extremely trivial statement that wealth cannot be created otherwise than during production, and that in circulation it can only change hands, I do not see what this assertion if the pre-eminence of production is supposed to mean.[4] The fundamental characteristic, the specific feature of the capitalist mode of production is separation of the means of production from the direct producers. This separation is produced by primitive accumulation and re-produced by the buying and selling at their value of the objective and subjective conditions of production. Neither of those operations has anything to do with production in the strict sense. The former is an affair of violence and looting, and the latter an act of market-exchange. To be sure, one can exchange (or loot) only what has previously been produced; but what is exchanged on the capitalist market is not necessarily produced under capitalist relations of production. In the course of its circuit, says Marx, industrial capital causes commodities to circulate which have their source in a variety of modes of production. “No matter whether commodities are the output of production based on slavery of peasants…, of communes…, of state enterprise… or of half-savage hunting tribes, etc. – as commodities and money they come face to face with the money and commodities in which industrial capital presents itself and enter as much into its circuit as into that of the surplus-value borne in the commodity-capital…” (Capital, Volume Two, Part 1, Chapter IV: London, 1958,p.110.)

This is how, accoding to Marx, “circulation takes hold of production.”[5] For it is through the process of circulation that the capitalist mode of production dominates the other modes, when they are combined with it in the same social formation. “It is the tendency of the capitalist mode of production to transform all production as much as possible into commodity production. The mainspring by which this is accomplished is precisely the involvement of all production into the capitalist circulation process” (ibid).

Put beside these clear statements, the few passages in the Grundrisse which seem to say the opposite merely reflect the vestiges of Hegelianism in Marx’s earliest economic manuscripts. Here is one of the most typical: “To the single individual, of course, distribution appears as a social law which determines his position within the system of production within which he produces, and which therefore precedes production. The individual comes into the world possessing neither capital nor land. Social distribution assigns him at birth to wave-labour. But this situation of being assigned is itself a consequence of the existence of capital and landed property as independent agents of production” (Grundrisse, London, 1973, p.96)

Here more than anywhere else the futility of the thesis in question reveals itself. What is “capital”, and, especially, property in land, and how can they exist outside of a very definite mode of distribution of the social product which ensures accumulation of the former by appropriation of surplus-value and constitutes the very content of the other, by deduction from what the peasant produces? Wages, profits and rents can certainly vary to a certain degree without the system of wage-labour and landed property being altered in essentials. But if these variations go beyond a certain limit, the system will be unable to reproduce itself. This limit constitutes the line of demarcation between reform and revolution. Nevertheless, whether it be reformist or revolutionary, the conflict between classes proceeds on the basis of the concrete distribution of the social product. The rest is mere verbiage.

Is it possible, moreover, actually to isolate the “instance” of production in the strict sense, what Marx calls the “labour process” or “the immediate process of production”? If one goes the whole hog and leaves circulation out of account altogether (and that means, also, some of its phases which, physically, take place inside the factory, yet have nothing to do with production), all that is left is the technical relations between foreman and worker. I do not see in WHAT way these relations can “dominate” the capitalist “structure”.

On the contrary, I see very clearly in what way and how the shop, the bank, the stock-exchange, places where nothing is produced, can dominate both production anD the “structure”, and how this domination increases as the system develops and perfects itself. It is easy to imagine the abolition of foremen and non-intervention by the capitalist or his lieutenants, in the immediate labour-process — something like a new system of domestic industry, or a sort of workshop sub-contracting based on piece-work. The essence of the capitalist social relation would not be affected. But if one were to touch the slightest element of the power of financial control, the system would suffer essential alteration, and if that power were to be abolished, nothing would be left of the capitalist mode of production. The capitalist system is the system par excellence in which everything depends on the market. In all the other systems that have existed or can be imagined, one consumes what one has produced, but in the capitalist system one can produce only what gets sold, and where and when it gets sold. Not where and when the conditions for production are most propitious and the prices of the factors mast advantageous – under-developed countries, low conjuncture – but where and when the prospects for sales are most promising — developed countries, high conjuncture.

But the pre-eminence of circulation follows also from two other points in the accepted doctrine: (a) Marx emphasises on several occasions that the labour-process is, on the one hand, a process of production of use-values, and, on the other, the moment when the direct producer is once more united with his means of labour.[6] These two facts do not seem such as to endow this “instance” with pre-eminent status in a mode of production which is essentially characterised by exchange-value and by the separation of the direct producer from his means of labour. As regards the former, saying that the labour-process produces use-values means saying that, in this process, labour is concrete and not abstract. “It is leather that gets tanned,” Marx explains in another place, “and not the hide of the capitalist.” Of course, no employer or foreman would fail to distinguish between Peter the welder and Paul the plumber in the organisation of work. It is in the sphere of circulation, outside the gates of the factory, that Peter and Paul vanish, giving place to labour which is undifferentiated, abstract, anonymous — “mere labour.”

As regards the latter of the two facts mentioned, although the labour-process differs from one mode of production to another, it is, in one respect, the same in all of them. This is the union between labour-power and its instruments, independent of the legal status of either. It is the way this union is effected that marks off a particular mode of production and thus shows, what its dominant “instance” is. In the capitalist mode of production this union is effected by the previous acquisition of the two components – labour-power and instruments of labour – by the same capitalist, on the market.

(b) In the circuit of capital Marx places money at the extremities, while the immediate production-process figures in it as an intermediate moment which interrupts this circuit and, in a way, suspends its course… “The process of production therefore appears to be only an interruption of the process of circulation of capital-value…” (Capital, Volume Two, London, 1958, p. 41.)[7]

From the reading of what Marx writes on this question it emerges that the circulation of capital, surrounding the process of production in the strict sense, conditions and dominates that process. It emerges also that when the labour-process begins, the act of exploitation has already taken place, in essentials, because the capitalist is already the owner of a definite quantity of labour-power. All that matters to him thereafter is to take delivery of his purchase by consuming it productively. “The capital-relation during the process of production arises only because it is inherent in the act of circulation, in the different fundamental economic conditions in which buyer and seller confront each other, in their class relation.” (ibid. p.30)

It is in the same order of ideas that Marx criticises classical political economy, which, because it looks upon capitalist production as the natural mode of production, placed it at the poles of the circuit (P—M-A-M—P’), so that it was the circulation phase, M-A-M, which seemed to be the fleeting moment that interrupted the process of production.

Pre-capitalist opposition to the capitalist system

It is curious to observe that those who uphold the idea of the pre-eminence of the production “instance” are the same as those who deny most vigorously the determining role of the development of the productive forces in human history. What, exactly, is involved here? What we have is, in fact, what Marx called, already in 1848, a reactionary criticism of capitalism. For there are two possible ways of criticising the capitalist system — that which proceeds from a post-capitalist standpoint and that which proceeds from a pre-capitalist, or “petty- bourgeois” standpoint.

Every time that solutions which go beyond the existing system starts to become dubious in tha minds of opponents of that system — and this is what has happened since the countries of “actually existing socialism” have ceased to serve as models — some of these opponents turn back towards earlier stages of history and find refuge in a certain idealisation of the past, which in the circumstances of today takes the form of a kind of Rousseauism – that is, in fact, opposition not to the capitalist system but to industrial civilisation itself. Against productivism, against consumerism, against modern technology, against nuclear power, against material well-being, and so on and so forth.

There is nothing new in this. From the petty-bourgeois anarchism of Proudhon, which Marx was opposing when he spoke of the reactionary criticism of capitalism, to the neo-Malthusianism of contemporary ecologism, via the various corporatisms, such as Mussolini’s, the purity of ancestral values acclaimed in Hitler’s Mein Kampf, the “return to the soil” which, along with the cult of traditional values and a certain pastoral tribalism, was preached by Pétain and the Vichy regime, and, closer in time to us, Poujadism – all this is in the last analysis, only a series of manifestations of the same attitude, the attitude of those who reject the present, and, because they do not see the future clearly, escape into the past.

Appendix

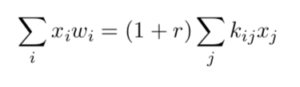

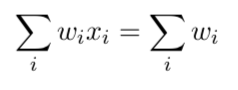

I refer here to a discussion with Ira Gerstein about Seton’s equations. This equation, which are generally accepted,

and in which:

wi = the labour-value of the product of branch i

xi = the factor of ” transformation” of commodity i

kij = the labour-value of commodity j, needed (as material input and/or as subsistence for the workers) in order to produce commodity i

r = the general rate of profit

constitute a system of prices which is perfectly determined except for a factor of proportionality, and so a system of relative prices. If and only if, we add the condition of invariance of the sum of values

do we obtain absolute values “transformed.”

But, apart from the demands of our own cause, nobody requires us to add this condition. If what is wanted is a mere standardisation, that is, a common denominator, for the convenience of having a cardinal number for each price, any other equation of standardisation would do the trick just as well: e.g.

wixk = 1 (money-commodity)

or xk = 1 (invariance of section III, according to Bortkiewicz)

or even ∑wixi = 150 milliard dollars

∑wiki = 3 milliard kilowatt-hours, etc. etc.

But all these conditions are adventitious. The real problem of Seton’s equations is to know whether a single set of rates of exchange and a general rate of profit can be found without any other data than the technical conditions of production, these inclading the subsistence needed for the Workers, and independent of demand. Given the hypothesis of constant unit costs, the answer is “yes”. And that is all that needs to be said.

Arghiri Emmanuel

Paris, 13 September 1982

- The most systemic and coherent exposition of this thesis is given by Henri Denis, in L’Economie de Marx, histoire d’un échec, Paris, 1980. ↑

- See the appendix. ↑

- In the same “absolute” terms the gross domestic product of China would be four times that of the U.S.A., and the world’s gross domestic product in 1982 would be exactly the same as in 1800, adjusted to allow for the increase in population between these dates. ↑

- We get a better idea of what it is supposed to mean when Right-wing governments also refer to the limitations of the “cake” produced, in order to moderate workers’ demands. The advocates of this pre-eminence of production repeat, moreover, with an air of saying something very profound, Marx’s wisecrack to the effect that even looting presupposes production of the thing looted. ↑

- It is in Chapter XX of Volume Three (“Historical Facts About Marchant Capital”), that Marx shows how, little by little, starting from simple commodity relations and feudal relations, circulation takes hold of production and how it is that the place of circulation is, in the capitalist mode of production, more determining than in any of its predecessors. ↑

- “Within the production process, the separation of labour from its objective moments of existence – instruments and material is suspended” (Grundrisse, London, 1973, p.364.) ↑

- On page 23 of the same volume, Marx had already mentioned that the dots he put after P signified that the process of circulation of capital was interrupted. ↑