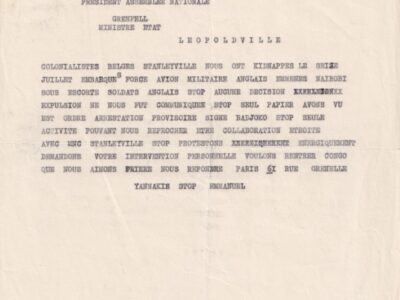

This is an article found in Arghiri Emmanuel’s archive, written on July 27th in 1961 after Emmanuel had been deported from the Congo by Belgian settlers. In it, he conducts an extensive analysis of the economy of the Congo at independence, the role of the settlers, and gives detailed advice to the Free Republic of the Congo, a Lumumbist government in the East led by Antoine Gizenga after Patrice Lumumba’s death.

1) The Congo before independence.

According to rough estimates, the Congo had, on the eve of Independence, an annual national income of +50 billion francs.

This revenue was divided approximately in half between the 110,000 whites on the one hand and the 14 million blacks on the other. Twenty-five billion francs assured the twenty thousand whites of the highest annual income per head on earth, the other 25 billion kept the 14 million blacks at the bottom of the scale of underdevelopment.

It was of course impossible to make the distribution of the Congolese income include whites and blacks in an undifferentiated manner. Apart from the entirely theoretical hypothesis of a lay apostolate, of a legion of “de Saint-Exupéry” (why not? It is with such legions that the Soviet Union is in the process of developing its deprived regions), a country like the Congo necessarily had to pay its foreign technicians at off the scale high prices.

But the retribution of the whites in the Belgian Congo had far exceeded anything that could be thought of as an expatriation bonus, and the luxury of the European setting had no parallel in any other African colony.

This luxury was especially accentuated after the last war. Trade union action, reserved at the beginning and for several years exclusively for whites, strongly contributed to this. This action had the backing of the CGTB and the PSB and at least the benevolent neutrality of our organizations. (I think we made the mistake of seeing in this action only the antitrust and the fundamentally reactionary position of the small settlers, salaried or not, had entirely escaped us).

This action mainly played on the benefits in kind so that any employee, first term, at the base salary of + 15,000 francs per month, cost his employer, depending on the region, between 35 and 45 thousand francs per month.

After 1954-1955 no more white people agreed to stay in an apartment. They all demanded and obtained villas with a rental value varying between 12 and 25 thousand francs per month. But it is not only by the exorbitant salaries that the white share of the national income became disproportionate. It is also by the number.

Because of racial discrimination, white people were needed in positions where no special qualification was necessary, other than the color of the skin, hotel reception desks, bank or transport company counters, store clerks etc. To satisfy the colonial client, it was necessary to have him served by a white man.

The massive Africanization that took place after Independence demonstrated that the whites were clearly oversized.

2) The settlers and their trusts.

This circumstance, i.e. the fact that 20,000 privileged citizens received national income as much as the remaining 14 million, could have given the independence movement a social content, concrete, clean, to mobilize the Congolese masses on a specific and immediate objective. Rarely in the history of revolutions have the demands of a people been presented in such clear and simple terms. The task for political leadership was easy. But this political direction failed and the 25 million in question, instead of constituting the objective of a mass movement, constituted the pole of attraction for a few thousand clerics, who did not last long. to understand.

All those who were interested in the Congolese problem before independence, only transposed into an entirely new and unprecedented situation formulas generated by the class struggle, such as it unfolds in countries of the traditional capitalist type. The result was aberrant.

“Equal pay for equal work”, an eminently progressive slogan in America, where 15 million blacks are paid less because of racial discrimination, applied to the Congo, where 20,000 whites were overpaid also because of racial discrimination, meant the perpetuation of colonialism with change of the color of exploiters.

The struggles against the trusts, enemy No. 1 in Europe, carried out in parallel with a policy of neutralization of the intermediate bourgeoisie and management of small personal businesses, applied to the context of the Congo, confused all the cards.

This struggle could have a different meaning from the time of the independent Congo period of Leopold II and during the first decades after the annexation, a period during which the trusts scoured the Congo, carrying away everything that could be extracted by the strength of the arms of the working forces. It was during this period that traditional structures within the clan were brutally dislocated, that portage was rampant because “human sweat was cheaper than gasoline”, the population was decimated by several million. From the rounding from the mechanization of the twenties and the relative stabilization of extra-customary populations, the givens of the problem have changed completely.

From this moment the big impersonal companies became, from the point of view of production, the most rational form of organization and from the point of view of the distribution of income, that which was the most bearable. Only a complete socialization of the means of production remained superior to them.

In the end, it was the only force which, within the framework of capitalism, could ensure the fastest expansion by external financing. The issues of new shares being each year greater than the dividends distributed, it can be said that the trusts not only reinvested their profits in the country, but constantly brought in new money.

In the end it was the only form, which could accommodate African management very willingly, and independence with more or less difficulty, depending on its degree.

On the other hand, the colonate, whose expansion coincided with this second period, and I include in this term both the employees and the “settled on their own account”, could not put up with anything, neither trusts, nor the metropolis, let alone Africanization and independence. As in Algeria, as in Rhodesia, as everywhere else, the settlers were the most retrograde and reactionary force. Only a secession from the metropolis and the constitution of a state independent “white”, of the type of South Africa or Australia, could save them. Which they did not fail to notice, concretizing it very early in an explicit claim. In terms of the economy and production, the colonate constituted a dead weight, if not a parasitic and harmful element. Competitive and anarchic sector, living on the margins of the dirigisme and the planning of the trusts, controlling only a small part of the economy, and therefore not very sensitive to the imperatives of the whole, seeking immediate profit, a great waste of labor and resources, the settlers also spent and invested a large part of their profits outside the Congo, thus causing an outflow of funds.

However, instead of recognizing the settlers as the No. 1 enemy and fighting it, a certain left saw in it a progressive force to oppose the trusts.

It is no coincidence that the “left” newspapers in the Congo, such as “l’Avenir colonial”, “Le Stanleyvillois” etc. – with the sole exception of the “Informant” were racists and colonialists, and it was not out of simple demagoguery that Catholics and Liberals, like “Le Courrier d’Afrique”, “L’Echo de Stan” etc., came out for the emancipation of blacks. These positions expressed a real conflict, a conflict between Belgium and its colonists, a conflict which, since the last world war, was in the process of conditioning the evolution of the Congo to a much stronger extent than the conflict between Belgium and the natives. Belgium, and when I say Belgium, I am naturally thinking of Société Générale, has seen clearly. As soon as the war was over, she proclaimed me that the Congo was not a colony of settlement, but of framing, and she began to take action, both economically (restrictions on land grants, recruitment etc.), then on the political level (surveillance of the ultras, expulsion of a few etc.).

It is necessary to believe that these measures were not sufficient, since finally Belgium lost the Congo following precisely the action of its colonists and its ultras, action triggered the day before and the day after independence.

It should be noted that when counting civil servants among the settlers, it should not be forgotten that the latter were solicited by a dual membership. As lieutenants of the metropolis, they naturally found themselves on the other side of the fence and were therefore constantly opposed to the settlers, but as “little whites” they felt – especially the junior officials – solidarity with individuals. At the time of the crisis of June-July 1960, when the bureaucratic link was suddenly broken, they went en bloc to the side of the ultras.

3) Labor law.

Under European occupation the evolution of native society was conditioned by two major facts: The brutal destruction of the tribal structures and the constitution in extra- customary place of a privileged class beside a relatively numerous proletariat. Colonialism based its indigenous policy on the notion of paternalism.

It must be said right away that paternalism as a system, which replaces the free labor contract with reciprocal moral obligations between men, is perfectly valid in itself.

If we disregard the rather short parenthesis of capitalist relations, it is indeed under this regime that man has lived for millennia and millennia.

The tribal society was a paternalistic society. The member of the clan does not conceive that one can sell his labor power against any remuneration. If the clan feeds him, it is not to pay him or even to reward him for his work, it is simply because he is part of it, and if he has to work all day according to the orders of the chief, it is not to have the right to eat, it is simply because as a member of the clan, he has the obligation to do so.

When the white man came with his payrolls, his workbooks, and his learned calculations, counting the hours and the days, the presences and the absences, the black ended up vaguely understanding that the more he worked, the more money he touched at the end of the week, but for a long time he refused to admit this system as the natural order of things. In fact he never fully admitted it. So he has always motivated his demands by his needs, rather than by the performance of his work or by the benefits he brought to his employer.

Even when later the clerics proclaimed the slogan “equal work for equal pay”, we can clearly see when reading their diatribes that basically, what concerned them and what they valued was not the performance or the quality of their work, but the fact that occupying a white post, they should have the same standard of living as the civil servant whom they had replaced.

When it is not a question of paid work, but of the sale of products, and when the natives are not entirely detached from their customary environment, then the weakness of the mercantile motivation in relation to the paternalistic notion is much more evident. Going to tell the inhabitants of a village that they are free to sell their products to the highest bidder makes no sense. What black people want to know is not what they can do, but what they should do, what is good to do.

If you tell them, moreover, that they can choose cotton, maize or coffee as a crop depending on market prices, they will take you for a dangerous madman, because everyone knows that a normal man cannot simultaneously and indifferently need three products as dissimilar as maize, cotton and coffee. The whites therefore had the idea of continuing the paternalism of the clan for their own account. But that’s where it all went wrong. Because the paternalism of the clan is exercised for the benefit of its members, and, if it was conceivable to seize this law of work and the resulting state of mind, to pass without transition from a primitive society community to a society community of a superior type, it was on the other hand completely excluded from camouflaging capitalist super-exploitation indefinitely by means of a style of life inspired by community society but artificially transposing outside of it.

Basically it is not paternalism, but the one who took the place of the mother, which was bad.

The native ended up understanding that he was simply deceived and that the white man was using paternalism to escape the disadvantages of its own system, whenever the law of supply and demand was unfavorable to it.

The abandonment of the unemployed to their fate ends up enlightening the blacks on the reality of this one-sided paternalism. Only once has paternalism been used for the benefit of the native himself, instead of that of the boss, it was the case of the “peasants”. So their success was indisputable. The rage of the settlers was on its side to the extent of this success.

4) The world of work.

The proletariat of the Congo was (for an underdeveloped country) very numerous. Before Independence, there were more than 1,100,000 employees.

There are three categories to be distinguished: The Elite, what were called “the clerics” – the manual workers of the extra-customary centers – the agricultural workers. Taking as a basis the average income per capita (Congolese), which was in round figures of 2,000.- francs per year, we see that the intermediate category of manual workers in the cities was normally paid, i.e. according to qualification, between 6,000 and 20,000 francs per year, with an average of around 10,000.

As there was roughly one worker per five inhabitants in the extra-customary centers (women not working and taking into account unemployment), it can be said that this category of workers was fairly paid, obviously taking into account the fact that we did not have to distribute all of the national income but only half, the other half being appropriated by the whites. On the other hand, the two wings, clerks and agricultural workers, were abnormally and disproportionately paid, some above, others below the national average.

The differentiation of the clerics had gone beyond everything that characterizes “labour aristocracy” in capitalist countries, it was no longer a stratum within a class, but a class apart, which not only was completely separate of the proletariat, but found itself in opposition to it, virtual opposition and latent before independence, open and irreducible afterwards. Thus the Léopoldville strikers formally demanded, two weeks ago, a reduction in the salaries of clerks.

Here is a novelty that should make us think.

Some of these clerks managed to raise a little capital and set up small businesses or even buy small plantations. It was negligible before independence, but after this movement amplified. There are now in the cities and there are several thousand black merchants, there are no limits to greed for profit – a new bourgeoisie artificially creates and from scratch, mercantile and adventurous, without faith or law, without any of those traditions which make the true bourgeoisie a historically valid class.

To take this band of traffickers for a national bourgeoisie, in the Marxist sense of the term, is in my opinion a serious error, and I have the feeling that this error was sometimes made, not only in the Congo, but all over the underdeveloped world. On the other hand, agricultural workers are grossly underpaid. Under pressure from the settlers, the Administration had accepted the principle of the difference in the cost of living between the city and the bush, a principle which did not correspond to any reality, the cost of living being in many cases higher in the bush, than in the city.

Thus the legal minimum was set at about half and sometimes even below half that of the city. On the other hand in Congo the legal minimum was not, as in Europe, a basis for calculating the range of wages, but the effective wage and in the plantations the general wage, a few capitas excepted. This means that while in the towns a labor market of the capitalist type was gradually established and unemployment appeared in recent years, the settlers continued to resort to recruitment, that is, to forced labour.

The concession of the land costing only a symbolic price, and mechanization being non- existent, the capital required to create a plantation was very modest. The whole thing was to know how to find labour. As in the days of the Romans, or in the days of Gogol’s “Dead Souls”, it was often the case that the clearest value of an estate was the number of indentured laborers. Moreover, this category of settlers, the planters, were the most parasitic. Their role was limited to making the blacks work on a certain extent of land, and to pay them about half, and very often even less, of what they would have earned on their own, if they were doing the same cultivation. at their home.

From the point of view of production and whatever may be said, European plantations have been a brake, rather than an accelerator. Coffee production in Ruanda-Urundi, where coffee is an indigenous product, increased after the war by about three times. On the other hand, that of the Eastern Province, which is almost entirely in the hands of European planters, increased during the same period by only 70-80%.

Of course in both cases work is compulsory – free labor in the fields is, when it comes to the Congo, a figment of the imagination – but what counts in the organization of societies is not the motivation of labor, but its productivity and the appropriation of its product.

Finally, another characteristic of this agricultural labor force is the fact that it has not completely broken with the customary environment. Randomly recruited, these workers go to the plantations, then they return to the clan, perhaps to leave later. There are many instances where these workers pay their wages into the clan’s common fund.

5) The army.

A last, but not least, factor in recent events was the military.

When one examines the reactions of what used to be called La Force Publique and is now called the National Army, one must take into account the following facts:

The recruitment of the army, which, like any other recruitment, was in no way voluntary, inevitably brought under arms the least interesting elements of the villages and the most turbulent of the towns, given that both the customary chiefs and the Administration of extra-customary centers took advantage of recruitment to get rid of all undesirables.

The moral and human quality of the recruits mattered very little to the white General Staff, which only asked for one thing: “that it bites and that it goes inside”. As in the military perspective the army is an end in itself, everything was subordinated to its effectiveness, it being understood of course that the effectiveness and the good behavior of the armies constitutes the supreme objective of humanity. Also, General Jansens stubbornly refused any idea of Africanization, which could have reduced the standing of the, of “his”, Force Publique by an inch.

This is not surprising – what is surprising is that all those who criticized or who still criticize General Jansens today, implicitly admitted the principle of efficiency and tried to demonstrate that with a year or two of course, black officers could be made as effective as whites. There obviously Jansen had the good part, because the effectiveness of an army on the ground, whether we like it or not, is not only a function of the military science of the officers, but especially of their prestige and their ascendancy , and those things, which, in the colonial climate, Belgian officers possessed from the outset because of the color of their skin, no accelerated course could have conferred on black candidates coming out of the ranks.

No detractor of General Jansens has, as far as I know, posed the problem in its true terms, namely that it was better to have a less efficient and less stylish army, than to put the Congo to fire and blood. After all, we can ask this stupid and simple question: what need did we have in the Congo for an army of the very first order? To fight against whom? Lebanon or Libya have armies that are far from having the efficiency and the style of the German or French armies or even of the Force Publique du Congo Belge. Does it prevent them from living?

But if we go to the bottom of things, we see that it is still once the monopolization of the revolution by the “clerics” which is the cause of the catastrophe which occurred in the aftermath of independence. The soldiers wanted the Africanization of the executives, it’s an understood affair, but what exasperated them was this fantastic festival of notables, who, overnight, carved out salaries of twenty, thirty and fifty thousand francs a month, who drove in Cadillacs and who took the places and looks of the colonialists they had just dislodged, while they were excluded from sharing the cake.

We thus always come back to the first and essential question: There was in the Congo an annual national income of some 50 billion. Whites took half. Africanization, which was to follow independence, normally made available a good part of these 25 billion, part which could be used both to raise the standard of living of the masses and to increase investments and the rate of expansion. But the masses were amorphous and unorganized. So it was the elites who rushed on thews 25 billion. The “clerks” with their know-how and their political momentum, the soldiers with their guns.

CONCLUSIONS – WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

I) Our position towards the ruling class

If socialist states and progressive organizations of the different countries outside the Congo must necessarily deal with the people in place, those who are called upon to work inside the Congo and have a political activity, as inhabitants of this country, must distance themselves from the caste of “clerics” and the newly rich, however genuine the nationalism and neutralism of some of them may be. If the economic slump continues, we must fear an uprising mass of which Leo’s strikes constitute the harbinger. It’s not just big salaries, it’s not just the black market, there’s also the corruption of officials, which has recently taken on a worrying extension. The mass rumbles: “Iko mka yabo” (It’s their time), we hear people say it everywhere. This fatalism can very quickly turn into an explosion and sweep away all the profiteers from whatever side they belong to. Someone will be able to provoke, guide or direct this explosion. It is not excluded that this someone is the UN. If such an eventuality occurs and if we cannot take the lead in this movement ourselves, we must at least be able to break away from our current positions.

2) The organization of our regions.

The immobility of the GIZENGA Government must end. The unification of the Congo may not be for tomorrow. While waiting for it the life of the five million men, who populate the Province, Orientale and Kivu, continues. Since dynamic solutions are hardly possible and even undesirable – world peace being a higher goal than the very fate of the Congo – the status quo can last for a long time. In this case it will be on the results obtained within the regions it controls, that the GIZENGA Government will be judged. We will certainly be able to continue its negotiations at the top and its maximum demands for the unity of the Congo., but that doesn’t have to prevent us, in the meantime, from managing our regions, as if it were an independent state, in the process of engaging in peaceful competition with the other states of the Congo. It is not even excluded that through this competition and the influence of the good management of our provinces, we arrive at the unification of the Congo more quickly and more easily than by frontal attacks and political tricks. Must therefore:

a) Create in Stanleyville, in all the branches of the administration, the replica of the higher authorities, which are centralized in Léopoldville and whose cut paralyzes the smooth running of current affairs. The central government must stop running in a vacuum. It must install its ministries and its central administration and nest them in the general hierarchy of the services. At the same time, it will be necessary to disconnect from Leo all the provincial services, as well as the banks, the parastatals etc., up to and including the private firms.

b) Flexible formulas must be found to reconcile the principle of the unity of the Congo with the need to move forward. Examples: We cannot issue a new currency because it is a secessionist measure. So we authorize one or more banks to issue bearer checks, or even bearer gold certificates. We cannot devalue the Congolese franc, but we can establish there are special bonuses on the purchase of foreign currency from exports and certain taxes on the sale of foreign currency needed for import, which amounts to a devaluation in fact. Etc., etc.

c) It is necessary to establish at all costs relations of good neighborliness with the three surrounding countries, i.e. CAR, Sudan and Uganda, this independently of the non-recognition from the GIZENGA Government by these countries. Uganda’s experience proves that a modus vivendi based on trade relations is not impossible. (I just got through a friend, trader in Bangui, the principle agreement from the CAR authorities for an export from Bangassou to the Congo of 50 tons of petrol). So far no serious effort has been made in this direction, except for a mission accompanied by one or two UN officials, which went to Kampala and which, it seems, was very well received. Obviously it would be necessary, in this order of ideas, to renounce once and for all clandestine adventures, as futile as they are dangerous, which poison relations with these countries, as was the case with Sudan….

d) Strengthened by the establishment of normal commercial relations with these countries, the GIZENGA Government will be more at ease to negotiate with Léopoldville, for all that concerns the use of the waterway and the port of Matadi, but then it will have to deal not on the current basis, either of the pro back discount goods and goods coming from and intended for the PO, in the customs and banking circuit of Léopoldville, but in the sense of transit and free zones in the ports of Léo and Matadi, the whole being cleared through customs at Stanleyville and being treated by the Banks of Stanleyville directly with the foreigner. As for interprovincial trade, we can deal with Léopoldville on a case-by-case basis and on a bilateral basis.

e) A new bank has just been founded in Stanleyville, entirely Congolese, the name of which escapes me. This bank must open an account in Switzerland, the only place where the Leo authorities cannot block, and finance the naked foreign trade by means of this account.

f) It was necessary at all costs to establish postal relations between Stanleyville and the outside world, without going through Usumbura or Léopoldville. (Perhaps it would be necessary to take steps with the International Postal Union of Bern). In addition, it is absolutely necessary to seek to establish an airline directly from Stanleyville to Cairo. We can offer this line to Sabena and if she refuses, go so far as to ban Usa-Stan and Leo-Stan flights, which in the present state of things are of no use to the GIZENGA Government.

g) Study the release of prospecting and extraction of alluvial gold by the inhabitants of the auriferous regions.

h) Leveling off tax revenue through the imposition of consumption taxes, which are easily collectible without audit staff and immediately profitable.

In tackling the management of the region controlled by the GIZENGA Government, it must be remembered that, even if the foreign trade comes to a complete halt, the whole of PO and Kivu can survive indefinitely. Indeed, higher self-consumption here than in Bas-Congo and Katanga reaches roughly 75% of economic activity. It is moreover this self-consumption that has saved the situation so far.

3) Funding for Expansion

To accelerate Congo’s expansion it is obvious that self-financing (reinvestment of profits) is not enough. External funding is needed. It can consist of private capital or in the form of aid from friendly states.

It is indisputable that no state-to-state aid can match the influx of private capital, when this influx exists and when parallel repatriation of funds does not compensate for its effects. This is exactly what happened during the colonial regime. The issues of shares and bonds of the various loans left a bonus on the payment of dividends, but this bonus was largely compensated by the repatriation of funds operated by the settlers. (There was indeed a contrary movement immediately after the war, a period during which small capital, for the most part “uncivil”, fled Europe and sought countries of refuge in the colonies, but after 1953 the conjunction of political and economic consolidation in Europe on the one hand with the fall in the prices of colonial products on the other hand, caused a massive return of this capital with the profits made in the meantime).

Today it is completely excluded to rely on a contribution of private capital. Sacrificing its fundamental objectives in the hope of inspiring confidence in private capital is currently the most aberrant policy there is. Even if the logic resumed in the Congo and we were rebuilding a colony as before, no one would put a penny in the Congo. On the other hand, it is not entirely impossible to interest even today the great financial capital, enjoying international political guarantees, for purposes strictly limited in space and in time. No general line of conduct can be traced on this question. Each specific case will have to be examined according to the conditions of the moment and the absolute will to safeguard not only the sovereignty but the economic and social future of the country. But a certain course of action is already clear:

a) No consideration of the colonists, except for the essential technicians, engineers, agronomists, doctors, economists, magistrates, and teachers, or on the contrary it is necessary to proceed to an urgent recruitment.

b) Be imaginative in seeking formulas for coexistence with the existing trusts in a highly planned economy moving towards socialism. Above all, we must grasp the idea that this coexistence is not excluded a priori. Several factors make it possible, among others the fact that these trusts are already half nationalized, the state holding a large portfolio and in many cases the majority, the existence of a multitude of parastatals, the fact that these trusts being precisely “foreigners” remain parallel and superimposed and do not have much influence on the evolution of Congolese society, finally the fact that the administration of the local government had already, by force of circumstance, established a regime of command economy and planning. It is also necessary to find formulas ensuring the reinvestment of profits, for example the constitution of an investment company, whose shares will be given as a dividend (stock dividend) to the shareholders of the trusts. As for the future, it does not look so bad, since the concessions, in particular all the mining concessions, expire before the end of the century. For example the Union Minière with all the operating material will have to be handed over to the Republic of Congo in 1990. We won’t even need nationalization. The expropriation will be done by the scrupulous application of the conventions.

c) Apart from this possible coexistence with the trusts, the only way to get out of underdevelopment can be counted on the aid of friendly countries and on human investment.

4) Human investment.

No human investment policy will have a chance of success if it is not based on popular momentum and no popular momentum can be created if it does not start from the collectivist structures of customary centers.

If these collectivist structures constitute an obstacle to the capitalist development sought by colonialism, they are an extraordinary chance for a popular power, which would tackle the task of building a classless society. It is foolish to believe that one must necessarily pass through capitalism before arriving at a superior regime.

Not only must the disintegration of the customary village, initiated by the colonial regime, be stopped, but conservation measures must be taken, going as far as the reintegration of the elements, which are only half removed, like agricultural workers. The primitive collectivism of the clan must constitute the nucleus of a higher collectivism, a kind of popular commune adapted to local conditions. The intermediate link in the chain could very well be the peasants created during the last years of the colonial era.

The first step to take will be to give the village back its vital space – which the colonial regime took away from it with the despoiling notion of “state land” and the multiple concessions and reserves – and encourage it to resume its ancestral methods of cultivation, the product of an experience and a balance several thousand years old, i.e. rotating, clearing, and long fallow periods, which ensured the vitality of crops before the arrival of the whites. The increase in productivity will be sought at the beginning by small improvements to the traditional individual tools, both those of agriculture, and especially those of hunting and fishing.

One has to get used to the idea that within the framework of human investment and self-financing of the Congolese economy, there is no immediate possibility of mechanization on a large scale and massive use of chemical fertilizers. At most we will be able to study, depending on the region, the introduction of the animal-drawn plow and the use of some local natural fertilizers.

5) The collectivist organization of the village.

To the customary village it will be necessary to add the existing “peasants”, the European plantations abandoned or taken over in one way or another, and a small satellite industry, mainly processing land products, coffee factories, shellers rice mills, oil mills, cotton gins, repair workshops, forges etc.

All possibilities of mechanization will be employed in these enterprises gravitating around the village, but the organization of these enterprises will be conditioned by the collectivist structures of the village. Installed as close as possible to the village, they will call on a floating and interchangeable workforce, a sort of commandos who will leave their families in the village and who will return there after some time to be replaced by others. There will be no commitment or individual salary. The company will enter into a contract with the clan, expressed in anonymous man-days and the counterpart will be paid in kind or in cash to the clan’s common fund. It is a system entirely compatible with the psychology of the blacks, who had practiced it on their own in many circumstances before independence.

On the other hand, taking into account the traditional division of labor in the customary villages, the work of the fields being exclusively devolved to women, and the men taking charge of the clearing, hunting and fishing, and that these are the latter tasks which are likely to be affected by the relative mechanization of the beginning, there will precisely be a surplus of male labor, which will be used by the companies mentioned above. The problem will naturally find on the spot and from case to case varied and unpredictable solutions but one can imagine for example that an industrial company offers to the village to clear with its bulldozers the part of the forest which this village needs cleared, in exchange for which a certain number of men from the village go to the factory to work for an agreed upon amount of time.

6) Urban unemployment

As regards the unemployed in extra-customary centres, the problem is more difficult. Hope to absorb these unemployed in the foreseeable future by the creation of new jobs in cities, is completely illusory.

It is to be hoped that when the villages, organized as described above, begin to prosper, when the People’s Government takes steps to replace certain mercantile and corrupt chiefs, who used the collectivist and paternalistic structures of the village for their own profit and that of the colonialist, one can hope then that a part of the unemployed of the those who are not entirely detached from their customary environment will voluntarily return to their villages. But a greater or lesser part of these unemployed live in extra-customary centers for a long time, sometimes for more than a generation and have therefore severed all ties with their clan.

Another part may be used in public works carried out without major equipment and requiring a lot of labour.

Eventually there will be a large surplus of unemployed people who cannot be absorbed. For those I see no other way than shock solutions. If we succeed in drawing them into popular momentum – without which there is absolutely nothing to be done – it will then be possible to organize them into separate popular communes and install them outside but near the cities from which they come. The operation, to succeed, must be free from any idea of salary or individual gain. Something like: “We’ve had enough of rotting in the city, of begging all the days of work, to humble ourselves, to live at the expense of our brothers. Let’s go ten miles away and shoot ten thousand hectares of forest to make a city of our own, bigger and prettier than Stanleyville. The state will help provide us a few bulldozers if there are any, for a few months, some material, enough to eat for six months, the time to grow our first peanuts, but it will be up to us to manage ourselves. We’ve got it all, we don’t have need anyone, we have our masons and our carpenters, our blacksmiths and mechanics, we will organize our own life, we will elect our leaders and we will appoint our policemen.” It will take or it will not take, but if it does, it will have an immense impact. I believe that it is an experience worth trying.

7) Transition from a dependent economy to a national economy.

It will be necessary little by little to reconvert the Congo’s economy to adapt it to its new condition as a sovereign country. Colonialism maintains the colonized countries in the system of monoculture or some export crops and the extraction of raw materials. This is the clearest part of colonialist exploitation, an exploitation which is carried out not only for the benefit of the colonizer but on behalf of all the industrial countries. When an industrialized country exchanges its products with an underdeveloped country, it actually exchanges one hour of national labor for 5, 10 or 15 hours of labor in the other. This exchange rate in turn prohibits the underdeveloped country from carrying out its own capitalization and emerging from underdevelopment. This cycle must be broken. There is of course no question of abandoning certain branches of production, which find in the Congo a favorable ground, but it is necessary to create others and to diversify the economy, always having in view, that above the notion of immediate profitability, narrowly conceived in the capitalist spirit, there is the concern to amplify the internal circuit of exchanges and to balance the economy.

8) The value of the currency

One must get used to the idea that the Congolese franc has definitely and irrevocably lost its value. Its official parity with the Belgian franc is entirely theoretical and fictitious. Congo’s economy, even if working at full capacity, could never have supported the current salaries of soldiers, officers and civil servants. These wages will continually put pressure on the franc. Reducing them is impossible.

The only solution would have been an official devaluation of the Congolese franc which would have established the balance without touching the nominal wage. But this measure is ruled out for technical and political reasons arising from the current division of the Congo.

On the other hand, the current system of a double rate for the franc, one official, the other free, which allows traders to buy products on the basis of 7.- francs per shilling and to sell merchandise on the basis of 14.- or 20.- is catastrophic. It’s a bonus for the black market and a penalty for honesty. It is a regime that both harms the producer and threatens to stop the production, and poor consumers, i.e. the vast majority of the population, to the sole benefit of a few traders and those who receive high salaries, not to mention the beneficiaries of bribes.

The only system capable of remedying this situation is that of differential prices by means of a scale of premiums on exports and another scale of charges on imports. Here is the mechanism:

All the currencies resulting from the export of the products will be obligatorily sold to the Office do Chance (to be created in Stan) and all glues required for the importation will be provided by the latter.

The Exchange Office, taking as a basis the official rate of 7.- francs per shilling, will buy the shillings from the exporters by paying them a differential premium, ranging from zero to five francs per shilling, depending on the product from which the shillings come, with a view to ensuring remunerative prices for producers. In return, the Office des Changes will sell these same shillings to importers at 7.- francs plus a differential surplus ranging from zero to 13 francs per shilling, depending on the nature of the imported item (first priority, semi-luxury, luxury) in the aim of offering everyone goods at prices proportional to everyone’s income.

Thus these measures will have the double result of cleaning up foreign trade, by ridding it of the current black market, and solving the problem of disproportionate salaries of civil servants.

*****

It is understood that all the measures recommended above will be in vain and may even turn against us, if all this does not lead to the creation of a nationalist and progressive party worthy of the name, party or any other organization of the Congolese vanguard within which the interests of the Congolese people can become the absolute criterion of any policy, and in which collective incorruptibility and infallibility will finally be at hand. Party or organization which can finally engender the organs and institutions which will ensure the supreme arbitration of the nation.

This is why all the specific options that will present themselves in the application of the recommended measures will be taken according to this objective.

If throughout my presentation I adopted the point of view of the technician, I realize perfectly that the problem of the Congo is not in the technical domain. In an antagonistic society – and unfortunately Congolese society, if it is not very advanced, has nevertheless already embarked on the path of antagonism – it is not a question of managing things but people. And that is politics. And it is only politics that can implement the two great imperatives that sum up everything: AUSTERITY and POPULAR MOMENTUM.

27.7.1961